Few individuals have had more impact on photography, not to mention on society itself, than George Eastman. In 1878, Eastman, then a young bookkeeper in the Rochester Savings Bank, read about Charles Bennett’s improvements to the gelatin dry plate process and began to produce his own plates. By July 1879, he had patented a machine for coating glass photographic plates. Combining income from the sale of licenses for the process with $1000 from local buggy-whip manufacturer Thomas A. Strong, he founded the Eastman Dry Plate Company in 1881. In 1889, the company introduced celluloid roll film, and in 1892, changed its name to the final form, the Eastman Kodak Company. The origin of “Kodak” has always been something of a mystery; the most accepted explanation is that Eastman, always fond of the letter “K”, composed the name on an anagram set with the help of his mother.

The first cameras were simple wooden boxes, with the shutter cocked by a string dangling out of the body. Nevertheless, the original model was a landmark achievement, being

No. 1 Brownie, circa 1901

small, lightweight, and having the simplicity of roll film rather than glass plates. Eastman was greatly aided in his camera development by Frank Brownell, a cabinet maker who turned to the manufacture of cameras in the early 1880s. Brownell designed most of the early Kodak cameras, and was responsible for the design of the famous Brownie cameras, which for the first time brought snapshot photography within reach of the masses.

Once Kodak was firmly established in the consumer mass market, Brownell was instrumental in helping Eastman develop folding roll film cameras that appealed to the more serious photographer. These early folding “satchel” Kodaks displayed a square body

No. 5 Cartridge Kodak, 1898-1907

with a drop front forming the bed and focusing rail, while the top opened. to reveal the roll film holder. While large and bulky, they established a style of camera that, starting around the turn of the century, was to evolve into the small folding camera that was to dominate photography for the next forty years. Film came in various sizes, ranging from the relatively small 120 negative to the mammoth 7″ rolls of 115, designed for 7×5 in. vertical images with the No. 5 Cartridge Kodak. Beautiful videos of these early folding cameras are available on Jos Erdkamp’s web site at http://www.kodaksefke.nl/.

While the box cameras were simplistic and cheap, and the large folding cameras filled the needs of the professional and sophisticated amateur, what was needed was a compact camera with more features than the simple box. The first camera to fill this gap – and, incidentally, to set the template for the next century of roll film camera production – was another of Frank Brownell’s creations, the Folding Pocket Kodak of 1897. This

Folding Pocket Kodak, 1897 (Courtesy George Eastman House Collection)

unassuming little camera, with its single speed shutter and simple f/11 Achromatic lens, displayed three groundbreaking features: it used a bellows to collapse into a compact form that truly fit a pocket or small bag, it could be quickly loaded with readily-available roll film, and it introduced the 2 1/4 X 3 1/4 (6×9 cm) image that is still the standard for medium format today. Subsequent evolution was rapid. By 1900, the drop front and focusing rail had replaced the struts of the original Folding Kodak (see Folding Kodak ad), and by 1902-3, models of the Folding Kodak were available with variable speed shutters and apertures, as well as

Subsequent evolution was rapid. By 1900, the drop front and focusing rail had replaced the struts of the original Folding Kodak (see Folding Kodak ad), and by 1902-3, models of the Folding Kodak were available with variable speed shutters and apertures, as well as

No. 4A Folding Kodak, 1906 (Courtesy George Eastman House collection). Note pull-out front standard, pneumatic shutter and aperture f-stop scale.

rising fronts for architectural work. This simple and functional design had a long life, with cameras of this type being manufactured well into the 1930s by both Kodak and many other manufacturers worldwide. Unfortunately, most of these beautiful old machines use film sizes that are no longer available and thus are strictly decorative.

Kodak Corporation had such a profound impact on the art and science of photography that it is easy to overlook George Eastman as a historical figure. A unique, caring and talented individual, he cared deeply about his many employees, frequently dispensing large portions of his considerable personal fortune to provide bonuses for his workers. His social philosophy, years ahead of his time, led him to institute a program of dividends and profit-sharing at Kodak. He was an extraordinarily generous philanthropist as well as an art collector. An extraordinarily creative inventor and innovator, he was one of the first American industrialists to employ a full-time research scientist. Plagued by serious ill health in his later years, he gradually gave away most of his fortune, wrote a note to his friends, and made the decision to take his own life on March 14, 1932 at the age of 77.

Given the millions of cameras produced by Kodak, with the multitude of models and the many lens and shutter combinations, the job of describing the best Kodak 120 roll film cameras for fine art work should be overwhelming – but it isn’t. Remember Kodak’s great experiment in the 1930s and 1940s (the heyday of roll film camera production) with 616 and 620 film? This axed Kodak’s contribution to today’s menu of usable roll film cameras. A list of Kodak’s models using 120 film is available on Mischa Konig’s excellent web site “Kodak Classics” (http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=206). It is shockingly short, and many of the models noted are simple box cameras, which makes Kodak’s contribution to the list of folding vintage cameras using medium format film and suitable for fine art photography very short indeed. Mr. Konig comments: “Kodak ceased production of 120 roll film cameras in the mid 1930’s, with the introduction of the 620 size, which is the same film on a slimmer spindle, and the only subsequent 120-film cameras from Kodak were manufactured in the UK in the 1950’s and ’60’s. The last 120-roll film camera from Kodak was probably the UK-made Brownie Cresta 3.”

Nevertheless, there are a few folding vintage Kodaks that use 120 film and take extremely high quality images; these all date from 1914 to the late 1920s. Much of the best work on this site has been produced with two such cameras costing a total of $40.00. For me, the greatest appeal of working with cameras of this vintage is the satisfaction proving that such neglected old relics can produce work that is of gallery quality in an era of multi-megapixel digital imaging.

Kodak’s designation of its constellation of roll film folding cameras is confusing, and different names were not uncommonly applied to the same model during the course of the production run. It is also important to remember that the numerical designation of many Kodak cameras in the 1920s referred not to the order of production but to the film size. An excellent source of well-organized information on early Kodak cameras and their complex nomenclature is Brian Coe’s Kodak Cameras: The First Hundred Years. An excellent description of Kodak lenses, unfortunately including only those from the 1930s on, can be found on Camerapedia at http://www.camerapedia.org/wiki/Kodak_lenses.

The most important consideration in deciding to purchase one of the many early classic Kodak camera is the lens. Many old Kodaks had only simple single-element meniscus

Meniscus Lens in Ball Bearing Shutter - Note Absent Front Lens Element and Bowl-Shaped Shroud

lenses. Meniscus lenses are identifiable by the presence of a metal front cover on the lens housing with a bowl-shaped depression surrounding a central opening and the absence of a visible front glass element. These lenses will not produce sharp images and should be avoided. The most common useful lens found on folding cameras of the 1914-1920 vintage is the Rapid Rectilinear, which, if used at apertures of f/16 or smaller, can yield stunning results. With cameras produced in the 1920s, look for an f/6.3 or f/7.7 Anastigmat. Less common lenses include the Tessars (either Bausch and Lomb or Zeiss), or, in the case of Kodaks manufactured in the U.K., the Ross Homocentric, Ross Xpres, Cooke Aviar (f/4.8 or f/6.3) or Cooke Series III.

Mention needs to be made of the Autographic feature, the 1920s equivalent of the modern databack. Found on many Kodak cameras until 1932, the Autographic feature consisted

Autographic Door, Pre-1916 Version on No.1 Kodak Junior

of an elongated door that opened in the back of the camera, exposing the backing paper of the film. Kodak Autographic Film permitted a message to be written on the film between frames. The spool was wound with a layer of carbon paper between the film and thin red backing paper. After taking a photograph, the user would open up the small door on the back of the camera and, using the provided stylus, inscribe a brief note. Pressure of the stylus on the backing paper transferred the carbon to the backing paper. The user then held the camera back to the light for a moment and light passing through would image the message on the film (http://www.clickondavid.com/no1a.htm). Different door styles were used through the years, and can be used to date Kodak cameras of this vintage; the image shown here is the earliest (pre-1916) version. For a full description of the Autographic feature, see Mischa Konig’s article on his Kodak Classics web site at http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=511.

Kodak Ad for Autographic Back (From the Photographic Times v. 47 (1915), courtesy Wikipedia)

Not only is the Autographic feature an important characteristic of early Kodak cameras, its story is fascinating in itself. During the early part of the twentieth century, Kodak absorbed a number of camera companies, gaining many important features and subsidiaries. These have been described in Rudolf Kingslake’s “A History of the Rochester, NY Camera and Lens Companies.” Kodak’s story intersected that of Henry Jacques Gaisman in 1914. Gaisman, the son of French immigrants, was too poor to attend college, but proved to be a capable inventor and canny businessman. After inventing the glass-enclosed bulletin board at age 16, he patented the design for the safety razor in 1904. This was eventually adopted by the Gillette Razor Corporation, and Gaisman became the head of the company after Mr. Gillette’s death. In 1914, Gaisman invented the autographic camera back, and immediately sold it to Kodak for the considerable sum of $300,000. George Eastman wasted no time incorporating this feature into his cameras, with the first autographic backs appearing by December of 1914. A further note on this fascinating man is that, after living into old age as a confirmed bachelor, at the age of 82 Gaisman married Kitty Vance, a 33 year old nurse. They lived happily together until his death at the age of 104 in White Plains, New York.

One important note in purchasing an early Kodak Camera: A No. 1 camera and a No. 1-A camera are not the same! The two designations, though sounding similar, refer to completely different film sizes. Kodak cameras designated as “No. 1”, except for the earliest models, use 120 film, while cameras designated as “No. 1A” take the discontinued 116 film, which was one of the most popular sizes during the 1920s. The dimensions of 120 are 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 in or 6×9 cm, while 116 is a much larger and longer negative at 2 1/2 x 4 1/2 in. The two models can be distinguished by the much longer body of the 1A camera.

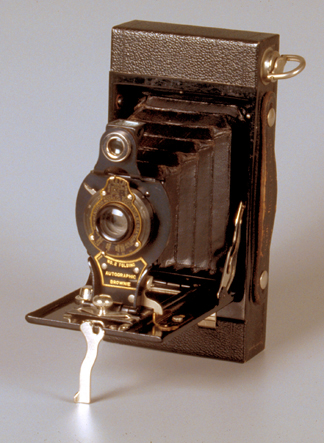

One of the earliest roll film cameras capable of doing fine art work is the No. 1 Kodak Junior, used to produce a number of the images on this site. First manufactured in April

No. 1 Kodak Junior

of 1914, the non-autographic version was discontinued in December 1914 after a production run of 33,000 in favor of the version with the autographic back, the No. 1 Autographic Kodak Junior. The latter was made until 1927, with a total production of well over 800,000.

The No. 1 Kodak Juniors were typically equipped with a meniscus lens or a Bausch and Lomb Rapid Rectilinear, the latter being most common. The above 1915 advertisement mentions the option of an f/7.7 Anastigmat lens; the number of cameras produced with this option must have been small, as they almost never appear on eBay. Many of the older models have the f/ scale calibrated in the old “U.S.” system in which the maximum aperture is designated as f/4, which translates to approximately f/8 in the modern system (see “The US f-Stop System” posting, which is in preparation). The shutter is a Kodak Ball Bearing Shutter with four speeds: 1/25, 1/50, T and B. The Kodak Ball Bearing Shutter is simple, unsophisticated, unlubricated (hence no oils to gum up) and virtually indestructible.

The camera is easily loaded by removing the J-shaped back. The small

plastic film counter window typically contains colored plastic of an orange tint. While this was adequate with the slow emulsions of the 1920s or the heavy paper backing of autographic film, it is too light for modern fast emulsions, and light leaks can occur. The easiest solution is to use a pair of tweezers to slide two layers of thin red plastic between the flat spring film flattening plate and the inside surface of the orange plastic window, and then glue the plastic pieces down over the window with a small amount of silicone rubber sealant. If the plastic is missing or broken, gently lift the outer leather covering around the opening on the back of the camera, and slide the red plastic between the leather and the aluminum back plate of the camera. The leather can be re-glued with white tacky craft glue, thus re-securing the backing and holding the plastic in place.

Once the front is pulled down to form the base plate, the front standard can be pulled out to extend the bellows. Focusing is by three small click stops at the base of the front standard. There is, unfortunately, no eye level finder. If the camera is in good condition, the only real problem that one not infrequently encounters with cameras of this vintage is deterioration of the silvering of the viewfinder mirror. One solution to this problem is to buy one or two extra No. 1 Juniors to use for parts (they are cheap, after all, with some going for $10-15 on eBay) and mounting the best mirror on the camera chosen for use. The viewfinder readily screws off by removing the chromed threaded ring holding it to the frame.

The No. 1 Kodak Series III is an excellent choice for a low-cost camera capable of making excellent images. My No. 1 Kodak is fitted with the 105 mm f/6.3 Anastigmat in a Kodex shutter with speeds of 1/10, 1/25, 1/50, 1/100, T and B. Focusing is accomplished by pulling the front standard out to the stop, then using the thumb screw at the lower left of the standard for fine focusing. As with the No. 1 Kodak Junior, there is only a waist level viewfinder mounted on the front standard. One interesting and decorative feature of this model is the rotating exposure calculator built into the aperture lever. For each f-stop, the engraved scale matches “DULL”, “GRAY”, “CLEAR”, AND “BRILLIANT” with the appropriate shutter speed. Calculating backward using the Sunny f/16 Rule (discussed elsewhere in this blog) indicates that the film intended for this camera in the late 1920s had an ISO rating of approximately 25.

Other, less common models to consider among early Kodak roll film cameras are the No. 1 Pocket Kodak, the No. 1 Pocket Kodak Junior, and the No. 1 Pocket Kodak Series II, some of which came equipped with the f/6.3 or f/7.7 Anastigmat. These were manufactured from the 1920s until 1932. A somewhat earlier model to consider is the No. 1 Autographic Kodak Special Model A, produced from 1915 to 1920. Only 18,000 of these cameras were produced, so they are encountered only occasionally. These were equipped with a variety of lenses including the Zeiss Tessar or a variety of Anastigmats made by Bausch and Lomb, Zeiss, or Cooke. UK variations may be found with a Cooke Aviar, Ross Xpres or Homocentric, or even a Lacour-Berthiot Olor Anastigmat.

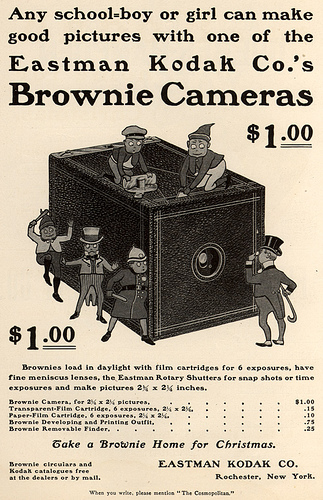

If one wishes the challenge of using a very early Kodak roll film camera, one might consider the No. 2 Folding Autographic Brownie. The Brownie series, inspired by George Eastman’s brilliant designer Frank Brownell, represents a separate and enormously successful branch on the evolutionary tree of Kodak cameras. It is unclear whether the Brownies were named after Brownell or Palmer Cox’s enormously successful cartoons and books about Scottish fairies, but Kodak borrowed extensively from Cox’s engaging cartoons in their advertising.

Designed as a simple box camera suitable for use by children, the first Brownie was made of cardboard and retailed for $1.00. From this early model (whose patent can be viewed at http://www.google.com/patents?vid=725034), the Brownie line expanded to a line of box and folding cameras produced into the 1980s that truly brought photography within reach of the masses.

The No. 2 Folding Autographic Brownies are very simple cameras, many of which were equipped only with a meniscus lens, but those provided with a Rapid Rectilinear lens should be capable of producing quality pictures. Note that a 120 film camera is “No. 1” in the regular line of Kodak cameras, and “No. 2” in the Brownie line. Unlike later roll film cameras, the Brownie is opened by releasing a sliding front catch and lifting off the entire front assembly bearing the baseplate, bellows, and front standard. The Kodak Ball Bearing Shutter has speeds of 1/25 and 1/50 sec in addition to T and B. focusing is by click stops at the front of the focusing rail. Many of these old folding Brownies will use the US f-stop system (see my posting on this topic). Dating the camera can be done by the presence or absence of the autographic feature (introduced in Feb 1916), a rounded case configuration (changed from square ended in Jan 1917), and the shape of the support foot (changed from S to C shape in Oct 1919).

NOTE: If you should wish to use a classic Kodak camera that takes 620 film, it is possible to respool 120 film onto 620 spindles. This is an inconvenience, particularly if one wishes to do any significant amount of photography. Alternatively, 620 film could at one time be purchased from Film for Classics in Rochester, New York. Their site is www.filmforclassics.com

References:

Baker, Chuck. “The Brownie Camera Page.” http://www.brownie-camera.com.

Bellis, Mary. “History of Kodak and Rolled Photographic Film. http://inventors.about.com/od/estartinventors/ss/George_Eastman.htm.

Camerapedia and Wikipedia articles on Eastman Kodak, Kodak Lenses, Henry Jacques Gaisman, Frank Brownell, and Palmer Cox.

Coe, Brian. Kodak Cameras: The First Hundred Years. Hove Collectors Books, West Sussex, 2003.

Cox, Palmer. “The Origin of the Brownies.” Ladie’s Home Journal, 1892. Cited in “The Brownie Camera Page”, http://www.brownie-camera.com/articles/origin/origin.shtm.

George Eastman House Online Collection. http://www.geh.org/technology.htm.

Kingslake, Rudolf. A History of the Rochester, NY Camera and Lens Companies, Online Posting, http://www.nwmangum.com/Kodak/Rochester.html.

Kodak Corporation web site. “George Eastman”, http://www.kodak.com/global/en/corp/historyOfKodak/eastmanTheMan.jhtml?pq-path=2217/2687/2689.

Konig, Mischa. “Kodak Classics.” http://kodak.3106.net/index.php. An excellent source for information on classic Kodak cameras.

Living Image Vintage Camera Museum. “Autographic Kodaks.” Online Posting. http://licm.org.uk/livingImage/Kodak-Autographic.htm.

Mc Keown, Jim, and McKeown, Joan. Collectors Guide to Kodak Cameras. Centennial Photo Service, Grantsburg, WI, 1981.

what an interesting read!

i have just in the last few days been given a No. 1A Autographic Kodak camera (i think it’s a 1A…) and really don’t know where to start.

i’m searching for some kind of “user guide” but so far having no luck.

but in saying that i’m glad i found some more information here!

hope one day soonish i will be able to post some photos from this beautiful camera!

Dear Seki Machihato-

Take off the back and look inside. Somewhere there should be stamped the model of the camera. Let me know what it says. I can probably help you out.

Best wishes,

Rand Collins MD

Mr. Collins,

Thank you for the article. I too have just come across an old No.1-A Kodak Junior and would love to be able to take photographs with it. However, I’ve run into an issue of obtaining the right film! Do you have any suggestions of where I can purchase some? Thanks much!

Adam

thank you for your reply!

i have looked inside the case however there is no model number stamped inside. I could see above the lens that it is a No.1-A; which i think uses the old 116 film.

any idea with regards to a step-by-step guide?

happy new year!

sekimachihato

Dear Seki-

For manuals, look on the Kodak Classics web site under manuals; you should find links to your camera or a similar model. The link is: http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=301. Also try out Mike Butkus’ page at http://www.butkus.org/chinon/kodak/kodak_1a_3_series_iii/kodak_1a_3_series_iii.htm. Check out the lens type: is it a Rapid Rectilinear or a meniscus lens? The latter is a simple lens and will not give as good results as the RR lens. 116 film is no longer available, and the camera takes a longer image than those seen with 120 film, so you will have to wind past the film numbers and do some guesswork. It is designed for a film that is 2 1/2 in wide; you can use 120 film, which is 2 1/4 in wide, in it, but you will have to craft a small spacer to put on one side of the 120 film roll so that the little teeth on the winder will engage. Overall, a fair amount of work. One alternative would be to use the 1A as a decoration and buy a No. 1 Kodak Junior on eBay for less than $20. This camera is designed for 120 film. See my posting on Kodak Cameras for other models that do not require as much adaptation, or my posting on Roll Film Cameras for alternatives by other manufacturers.

Great article, thanks a lot! Your links are great but I am still trying to figure out which lens I have on one I was just given as a birthday gift. It used to be my grandpa’s and I don’t have it with me at the moment.

I know it is a No. 1; not an A.

Exposures at 1/25, B, T, 1/50

4 f stops numbered as f stops not 1-4.

3 focal distance notches (I think)

The engraving around the lens is super ornate.

It is serial 97xx and has two patent dates on the lens, something like Jan 13 1913; one other.

Says Eastman Kodak Rochester NY around the lens.

Any help would be great!

Dear Daniel-

Thanks for the photos. Your camera is a No. 1 Kodak Junior with the autographic feature (the small door on the back). The lens is a Rapid Rectilinear made by Bausch and Lomb. A link to a description of this camera is available at:

http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=206&cam=1131.

This description is, however, for the early, non-autographic model (the same camera but without the small rear door). The model with the autographic feature was produced from December 1914 to January 1927, with a total production run of over 800,000. For a description of the autographic system, see:

http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=511

Your lens and shutter combination was produced from 1914 to 1924. Your style of autographic door was produced from December 1914 to March 1916, so I would place your camera within that two year span.

Serial number at the beginning of production of this model in December 1914: 33901. Serial number March 1916 when autographic door changed: 94,701. This should allow you to pin down a more exact production date.

Note for taking pictures: This camera’s lens uses the old U.S. f-stop system, and the Rapid Rectilinear is not an f/4 lens, but rather an f/8 lens. See my posting on “The U.S. f-stop System.”

Good luck with the pictures! Keep me posted.

Thank you so much for all of the info! I would say my camera was made in December 1914 as it is serial # 33911. That makes it the tenth one built of this model produced, correct? I’ll let you know when I get the first few rolls processed.

My name is Piter Jankovich. oOnly want to tell, that your blog is really cool

And want to ask you: is this blog your hobby?

P.S. Sorry for my bad english

What a great read! I found your pages whilst researching for my two vintage Kodaks – a Vest Pocket Model B Autographic (27323, pre-1930 I think) and a No 1. Pocket Junior (16069 with an f/6.3 Anastigmat lens), interesting to learn the Junior is not that common and I guess, from the serial number, that this another 1920s camera?

I have yet to buy any 127 film (I fully intend to) but am currently putting my first film through the Pocket Junior. That “brilliant” viewfinder is anything but!

Thanks for your nice comments. I agree about the viewfinder; try using it for night work! If I can be of any help, please do not hesitate to e-mail me at randcollins6@yahoo.com. Some of the old lenses are surprisingly good with color too, probably because they are of simple design with few elements.

This is very interesting reading. Thanks so much for the info. I’m wondering if you can help me finish identifying when my camera was made.

It’s a No.1A Kodak Junior. Based on information on your site and the links, I have somewhat narrowed it down.

– Rapid rectilinear lens + a Kodal ball bearing shutter = 1914-1925

– The particular autographic door was produced from March 1916 – Sometime “during the 1920s” according to this link: http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=511

– The latest patent engraved into the back plate is June 19, 1917.

– You mentioned that “Many of the older models have the f/ scale calibrated in the old “U.S.” system in which the maximum aperture is designated as f/4” –But, what do you mean by “the older models”

– This model was produced by Canadian Kodak Co. in Toronto.

I was hoping you could help me narrow it down, perhaps by the serial number. However, there are a few different numbers that could potentially be SNs, and I’m not sure which one is the actual camera serial. Could you tell me where exactly to locate it?

Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Thanks

Katie

–

A used No. 2 Brownie is not very valuable – I would say under $20.

Hello M! Well first, you need to consider which type of film you will be using. Basically there are two types of films you could use, either the 120mm (a.k.a medium format film) or the regular 35mm film. This shouldn’t be a problem since medium format cameras such as Holga & Diana can be modified to take a 35 film, and to me that’s an advantage. I haven’t tried the supersampler yet. It looks mighty fun But I wouldn’t recommend it a lot since there isn’t much of modifications you can do to it unlike the Diana. As for the fish-eye camera, I would suggest getting a lens instead of the whole camera. This way you can have both a regular and a fish eye camera at the same time. Assuming that you live in Kuwait, keep in mind that medium format films aren’t very accessible here. As a matter of a fact, I only found one place that still sells 120s but they only had one kind film & unfortunately it was Fuji pro 160.Since you’re new to photography, I would suggest either getting a or a with their (just in case you wanted to use a regular film) and get your film supply from .If you have any more questions, feel free to ask. I’d be glad to help a future fellow lomographer -Nada

I have just inherited a Kodak camera that I would like to date and value it. It’s a #1 anastigmat F6.3. . Would appreciate any help from you. It appears to be in great condition.

My last posting I forgot to ask about another Kodak camera I came across. This one is also in very good condition. It is a Kodak Signet 35 . Could you give me a value and age of this camera?

Thank you

Jim

Dear Jim:

According to McKeown’s Price Guide to Antique and Classic Cameras, the Signet 35 with the Kodak Ektar f/3.5 44mm lens and Synchro 300 shutter was produced 1951-58. My 2005-6 edition values it at $100-150, so it might be a bit more in 2012. A Signal Corps model was made; its value was $200-300.

As far as the Kodak is concerned, the “f/6.3 Anastigmat” describes the lens, not the camera – lots of people make that mistake. No. 1 means it takes 120 film and is potentially usable today. The f/6.3 Anastigmat is a very sharp lens and my image of Somenos Marsh as well as a number of images in the Palouse were made with that lens.

However, there were a bewildering number of “No. 1” Kodaks with many lens/camera combinations. Can you send me pictures of the front and back closed, as well as the front open, plus information about what is written in the front of the camera (such as “No. 1 Pocket Kodak, Model III) A close-up of the patent dates from inside the back might also be helpful. Also, does it have an Autographic back (little flap or sliding window on the removable back plate)?

This is interesting. I’ll look forward to hearing from you.

Best wishes,

Rand

Attached are pictures of our old Kodak camera. This is Six-16 Kodak, w/Kodak Anastigmat Lens f.6.3. The patent numbers inside the back cover are; 1227,226, 1610,175, DES82976, 1857,502, 1402167, 1870,620, 1435646, 1908,531. Canada 1931-1932. Printed in USA , No. 53007. We will wait to hear from you. Jim Schaaf

Dear Jim:

The Kodak Six-16 looks to be in lovely condition!

What you have is a Kodak Six-16, “Improved” model, manufactured 1934-36.

The Six-16 line was designed for the new 616 film and introduced in 1932, first with a pull-out front standard that did not pop into place automatically. This was the old style but it worked well. The first self-erecting model was produced 1932-33, but the design of the struts was different and, although they were lovely to look at, they were truly a pain in the neck to fold down, and the parts didn’t slide well. I know – I have a camera with these struts on it, and I open it up only when I absolutely have to. Consequently, the new, simplified struts were “Improved” and were probably greeted with sighs of relief.

Value is listed at $40-60 in 2005 McKeown’s, possibly a bit more in 2012.

This is a very usable camera with a good lens, EXCEPT for the 616 film. Kodak made a great experiment in the 1930s and 1940s with 616 and 620 film, which were basically good old 120 film in a slightly slimmer spool. This may have forced people to use Kodak film, or it may have been an effort to make a slimmer camera, though the slimmer spool only gained a few millimeters. Using the camera today means grinding off the rims of every roll of 120 or re-rolling it onto 616/620 spools, which is really not worth it.

However, it is a very nice, decorative camera with beautiful Art Deco styling. Enjoy!

Best wishes,

Rand

Hi, I have a No 3-A Folding Pocket Kodak

Can you tell me the value?

U.S Patents

Jun, 21 1808, Sep 20, 1898, Oct 8, 1901,

Jan 21, 1902, Apr 29, 1902, July 8, 1902,

Sep 9, 1902, Sep 7, 1909, Oct 19, 1909

Jan 18, 1910 Jun 16, 1914

Other Patents Pending

Really enjoyed reading the information you provided.

Thank you

Dear Cheryl:

I do not have McKeown’s Price Guide with me at the moment, but I would guess a 3A Pocket Kodak at about $25-30. Some of them are lovely cameras if well preserved, but they were produced in enormous quantities and consequently are quite common. A check of eBay revealed many of them for sale, but few selling. There are some Kodaks that are quite valuable, but they tend, like upside-down American coins or stamps, to be very early or unusual models produced in small quantities.

However, enjoy your camera; some are well preserved and make wonderful family heirlooms!

I enjoyed the info on your site, excellent job! I recently purchased a No.1 Autographic Kodak Jr. at a yard sale and have shot one roll through it. I used Ilford XP2 Super film and had about four decent pictures turn out. The edges of my lens appear to be seperating internally and I would like to find a new one if you know of any sources? Also, can you give me a brief tutorial on the settings I should be using as far as shutter speed and aperture size? Thanks for any help

Dear Matt:

Thank you for reading!

First, remember that your aperture settings are probably not modern f-stops, but are most likely in the old “US” system. See my article on the Universal System on the site.

Next, you ideally need a light meter, but you can make do in daytime using the Sunny f/16 rule. See my article on this topic. To estimate other lighting situations, Fred Parker has published “The Ultimate Exposure Computer” on his site at:

http://www.fredparker.com/ultexp1.htm#usethrow

which gives exposure values for all kinds of lighting conditions. Remember, people used to do this kind of estimating for all of their photography before light meters became part of cameras, and every roll of Kodak film used to come with a little exposure table inside the box.

The edge separation may not be a problem if it is only peripheral. The Rapid Rectilinear lens needs to be used significantly stopped down to be sharp – at least f/11 or better f/16 – so problems around the edge of the lens may have no significant effect. The No. 1 Junior that I use as a working camera has about 1 mm of edge separation and takes extremely sharp images.

I shoot XP-2 at about ISO 200, i.e., by the Sunny f/16 Rule, f/16 at 1/200sec. Since you don’t have 1/200 sec, use 1/50 sec, the fastest speed, at f/32. Since the f-stop and US system intersect at f/16 = US16, count up two stops from US16 on the aperture scale to US64,which is f/32. Do not attempt this calculation this after more than three drinks or when running from a lion.

Since you need to use small apertures, you will find yourself guesstimating lots of one and three second exposures in reduced light circumstances. A digital watch helps. Bracketing by two stops on each side helps, and when in doubt, overexpose.

Make sure the autographic door is closed – they leak light if bent or allowed to gape a bit. if you can pick up one of early 1914 pre-autographic models, this problem disappears.

Buying a second Junior is good insurance for spare parts, but they are really remarkably sturdy little cameras if well cared for.

Good luck – love to see the results.

A trade secret: go to the Astronomy Tools site and buy Noel Carboni’s suite (about $20) that has Local Contrast Enhancement on it. I never used the rest after installing it on Photoshop, but LCE really spruces up images.

Best wishes,

Rand Collins

I apologise for taking up your time but cannot seem to find the info on the Mischa Konig website to date my camera. Mine is a No 1 Autographic Kodak Junior serial number 424425 made in Rochester. 120 film. Apertures to f4 to f 64 ( old style I guess). Ball bearing shutter marked 25 a T and 50 ( ‘a’ is what I call B). I would like to find out the age and also the lens type then would like to try using it but need to know how to roll a modern film on as I believe the numbering has different spacing?

Dear Malcolm-

I am travelling, so do not have access to my references; on returning home in three days, I should be able to roughly date your camera and give you some thoughts on using it.

My friend Rand

True I own your old camera museum but when I looked at your hobby to the revival of the life of the new lenses in order to pick up a new life I felt that what I’ve done I’m not in vain Yes we Andjema cameras prepared and forms, I was just entirety because it was and still is a witness of the times and assure you on that thank you

Dr. Khalil