Bill Carter, master jeweller

Wandering down the narrow, branching streets of old downtown Nanaimo will take you past the ornate stained glass of Bill and Jean Carter’s Bastion Jewellers. Bill …”practices traditional jewellery making the old-fashioned way. He carves master models out of wax to create custom designs then hand-fabricates the piece which gives him the freedom to make exceptionally beautiful, high-quality finished jewellery. Whether it’s a favourite logo, ring design, or an art-deco reproduction of an antique item, we create custom items in gold, silver, platinum, or a new blend of platinum-silver.”

Bastion Jewellers Storefront – A work of art in itself

Yet it is Bill himself who is the gem of the shop. I first met Bill bent over his immaculate workbench, carefully dissecting the workings of a classic mens watch. He was kind enough to sit for me. The little Ensign 16-2 is compact, and ideal for unexpected opportunities. I had no tripod, so braced my body as best I could, firing off two shots at 1/25 sec., slow exposures for a 75mm lens used without a tripod. However, one exposure was almost perfect, capturing Bill at his workbench.

This image will be part of a series on craftspeople in their workplaces, and is an excellent example of the genre known as environmental portraiture. No, this does not mean placing your subject beside a polluted river. Rather, it refers to the concept of photographing subjects where they work or where they spend much of their time, and its techniques differ sharply from standard portraiture. In traditional studio portraits, the background is de-emphasized, and is frequently shot out of focus by using the lens wide open and blurring any background details.

In environmental portraiture, deep depth of field throughout the images is maintained by the use of small apertures, and the subject is shown in his world, with all of his or her surroundings in sharp focus. Consequently, both the subject and his world are given equal weight in the image; one sees the subject as a part of his world and the activities that best define him. Following this idea further, David Peterson suggests having the subject actually perform his work to lend an extra layer of reality and impact to the image. Wonderful examples of this genre, together with excellent suggestions on camera technique, can be found on DePaul University’s “Environmental Portrait” page.

The greatest master of this genre was Arnold Newman, who posed the famous in their favorite environments: Georgia O’Keefe against a New Mexico bluff and a bleached steer’s skull, Igor Stravinsky at his piano, Woody Allen writing in bed.

Igor Stravinsky at his Piano. Arnold Newman, 1946.

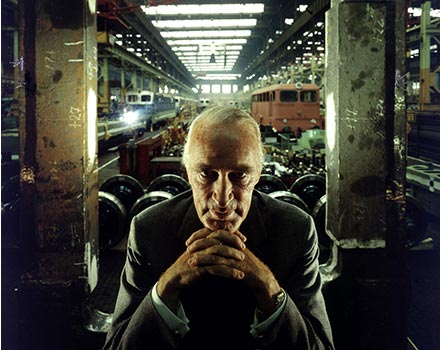

Andy grunberg notes Mr. Newman’s best-known images were in black and white, although he often photographed in color. Several of his trademark portraits were reproduced in color and in black and white. Perhaps the most famous was a sinister picture of the German industrialist Alfried Krupp, taken for Newsweek in 1963. Krupp, long-faced and bushy-browed, is made to look like Mephistopheles incarnate: smirking, his fingers clasped as he confronts the viewer against the background of a assembly line in the Ruhr. In the color version his face has a greenish cast.

Industrialist Alfried Krupp, Essen, Germany, July 6, 1963. Arnold Newman

The impression it leaves was no accident: Mr. Newman knew that Krupp had used slave labor in his factories during the Nazi reign and that he had been imprisoned after World War II for his central role in Hitler’s war machine.

References:

“Arnold Newman.” Wikipedia article. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnold_Newman.

DePaul University. “Environmental Portrait.” http://facweb.cs.depaul.edu/sgrais/environmental_portrait.htm.

Getty Images. http://corporate.gettyimages.com/marketing/m05/edit_newsletter/index.aspx?language=en-us&gi=2&pg=11

Grundberg, Andy. “Arnold Newman, Portrait Photographer Who Captured th Essence osf his ubjects, Dead at 88.”. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/07/arts/07newman.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

David Peterson. “Environmental portraits. What are they? How are they different?” http://www.digital-photo-secrets.com/tip/1982/environmental-portraits-what-are-they-how-are-they-different/.

The Arnold Newman Archive. http://www.arnoldnewmanarchive.com/.