Palouse Falls and Canyon (iPhone panorama)

Nestled in southeastern Washington is an area virtually unknown to tourists, but known and cherished by photographers across North America: the Palouse. Covering 3-4,000 square miles, predominately in southeastern Washington, but including parts of northern Idaho, and (according to some definitions) northeastern Oregon, the Palouse includes some of America’s most unique and picturesque farmland. Also the site of one of North America’s greatest cataclysmic events, it presents ever-changing contrasts, with rolling croplands, historic weathered farms, sculpted badlands, and golden afternoon light.

Panoramic View of the Palouse from Steptoe Butte. Courtesy L. Suckow, 2006

Palouse vistas are of two types: farmland and badlands. Highways through farming regions pass seemingly endless dome-shaped, rolling hills, contoured with bands of golden, green, or yellow crops, with weathered farmhouses, silos, and barns peeking over their crests, and arcs of wheat rows or stubble. This area, beautiful in its unique colours and lines, is immensely photogenic, with a new image appearing over the crest of every hill. Inns and motels here are crowded every June when the crop colours are at their best. Fifty miles or a hundred miles later, the character of the land changes: the rounded hills become teardrop-shaped as if pulled like giant taffy; at the next turn of the road, enormous arc-shaped slices have been removed from these symmetrical domes, as if a giant sampled a box of chocolates. Driving farther, ragged coulees, canyons, and potholes appear, and the land looks as if it was scoured to the bedrock by a giant claw. These are Washington’s badlands, known as the Channeled Scablands, testament to a cataclysm of Biblical proportions.

Canola Field and Farmhouse near Colfax. Voigtlander Avus, Kodak VC-160

In either area, one of the most striking characteristics of the Palouse is its ever-changing nature. Return monthly or even hourly to the same hilltop, and you will find a different image with every visit. In early summer, the Palouse is a vibrant patchwork of rolling hills, covered by multicolored fields of green spring wheat and brilliant yellow canola; classic farms, silos, and barns dot the landscape as you can see a Trailside Horse Barn or a huge silo every couple of miles and narrow roads snake through the valleys.

Palouse Farm. Voigtlander Avus, 105mm Skopar Lens, approximately f/16, Kodak VC-160.

Later in the year as fields ripen, greens yield to a palette of rich yellows, multiple hues of gold, and the full spectrum of earth tones . All colours and contours change as the light shades from the harsh spotlight of noon to the warm hues and elongate shadows of the evening sunset.

Palouse Fields Near Colfax, Voigtlander Avus

Weathered farms and silos dot the hills and valleys, and harvesters trace dusty lines of stubble across the golden fields. Fence lines, tractors, telephone poles, solitary gnarled trees, and windmills make dramatic silhouettes against hillsides and sky.

Palouse Windmill. Digital image.

When winter comes, vibrant greens and yellows yield to browns, greys, and blacks. Lines of stubble and tractor tracks meander across hills in curves just made for dramatic black and white images. In any season, zooming into one of these vistas reveals abstract images from converging lines of sky, field, furrows, and earth.

Palouse Fields and Sky, Voigtlander Avus, Kodak VC-160, B&W conversion from colour image

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY:

The pastoral hills and croplands of the Palouse hide a geological mystery, and the badlands, gnawed and scoured as if by the death throes of some ancient beast, are a testament to Nature’s capacity for savagery. This story, which unfolded unfolded over a half-century of academic infighting and dogged persistence by one tenacious geologist, dramatically changed the science of geology.

The Palouse hills themselves, dome-shaped and separate, are unique and very different from the ridges and weathered formations found elsewhere in the state. Formed over millions of years, they are in reality giant dunes, formed from wind-blown silt, or loess, probably blown in from flood plains to the southwest or originating from volcanic eruptions in the Cascades in prehistoric times:

Dust Storm in Eastern Washington (NASA Satellite Image). Courtesy NASA and Hidden Journeys.

Channeled Scablands, courtesty Tom Foster’s site, HUGEfloods.com

Yet covering hundreds of square miles north, west and south of the fertile hill country, large areas of central and southeastern Washington resemble a moonscape. The first signs are hills that are gouged, molded or contoured. Deeper into the badlands, the rolling contours are pocked with deep coulees, potholes, canyons and valleys. Soon the farmlands become a barren wasteland of rocky outcrops and canyons. This territory is a vast (estimated 1,500-2,000 square miles) region, gouged, eroded, and largely denuded of soil, known as the Channeled Scablands. Characterized by steep-sided, square canyons and flat-topped buttes or mesas, this unique region includes mysterious ancient rock walls such as Dry Falls, that are reminiscent of waterless cataracts dwarfing present-day Niagara.

Dry Falls (Courtesy Wikipedia)

The landscape is littered with boulders called erratics, some very large, and most structurally dissimilar to any nearby geological structures. Other dry features include plunge pools, eroded bowls at the base of dry cataracts, that are suggestive of ancient cataracts.

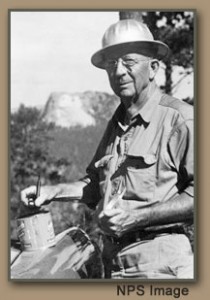

For years, these structures were considered to be the result of slow changes wrought by wind and water – at least until 1922, when the persistent, creative, and irascible geologist J. Harlen Bretz drove a borrowed Model T Ford into the area he was to christen the “Channeled Scablands.” An original thinker, Bretz quickly realized that these unique features, with areas scoured free of soil down to the basaltic bedrock, could only have been created by a flood of cataclysmic proportions. Publication of these ideas, described by one contemporary as an “outrageous hypothesis”, in 1923, sparked an acrimonious academic dogfight that was to leave Bretz embattled for the next 40 years. This story has become one of the classics of modern geology and has been expertly related in a number of sources (see HistoryLink and Soennichsen). Interestingly, Bretz never seemed that concerned that the source for this mass of water had not been determined.

For years, these structures were considered to be the result of slow changes wrought by wind and water – at least until 1922, when the persistent, creative, and irascible geologist J. Harlen Bretz drove a borrowed Model T Ford into the area he was to christen the “Channeled Scablands.” An original thinker, Bretz quickly realized that these unique features, with areas scoured free of soil down to the basaltic bedrock, could only have been created by a flood of cataclysmic proportions. Publication of these ideas, described by one contemporary as an “outrageous hypothesis”, in 1923, sparked an acrimonious academic dogfight that was to leave Bretz embattled for the next 40 years. This story has become one of the classics of modern geology and has been expertly related in a number of sources (see HistoryLink and Soennichsen). Interestingly, Bretz never seemed that concerned that the source for this mass of water had not been determined.

J. Harlen Bretz (NPS Image)

The answer to this last part of the puzzle came in 1940 from the patient work of U.S. Geological Survey geologist J. T. Pardee. As quiet as Bretz was outspoken, Pardee spent most of his career studying the deep valleys of northwestern Montana, and in 1910, based on traces of ancient shorelines on the mountains of western Montana, postulated the existence of glacial Lake Missoula, with a surface area of 3,000 square miles and containing up to 600 cubic miles of water. At the dramatic conclusion of a 1940 meeting designed to debunk Bretz’s flood theory, he quietly confounded Bretz’s critics with his presentation on giant ripple marks, particularly in the Camas Prairie region, that could only be consistent with a cataclysmic prehistoric flood. Combining Pardee’s work on Lake Missoula with Bretz’s observations led inescapably to the conclusion that this lake had flooded the northwestern states, probably as a result of the failure of an ice dam. Aerial photographs and later satellite imagery silenced the critics, confirmed Bretz’s theory, and provided the basis for interpreting similar enormous flood channels on Mars.

The wall of water that raced across northern Idaho and eastern Washington is estimated to have been 2,000 feet high and to have contained more water than the combined flow of all of the present waters of the world. It smashed its way to the Pacific Coast, covering Oregon’s Willamette Valley and inundating present day Portland under 400 feet of water. Present theories suggest that this flooding process may, in fact, have happened many times.

Even more profound than the waters’ ravage of the northwestern United States, Bretz’s flood changed forever our understanding of geological processes. At the time that Bretz proposed his theory of a catastrophic flood, geology had for two centuries been firmly rooted in Charles Lyell’s theory of uniformitarianism, which postulated that all geological processes occurred gradually over time. Acceptance of Bretz’s flood introduced the concept of intermittent catastrophic events punctuating the slow progression of geological changes.

EXPLORING THE PALOUSE:

A Palouse experience should really start with camping at Palouse Falls State Park. Pitching a tent under the shade of a tree on this grassy bluff at the lip of Palouse Canyon,

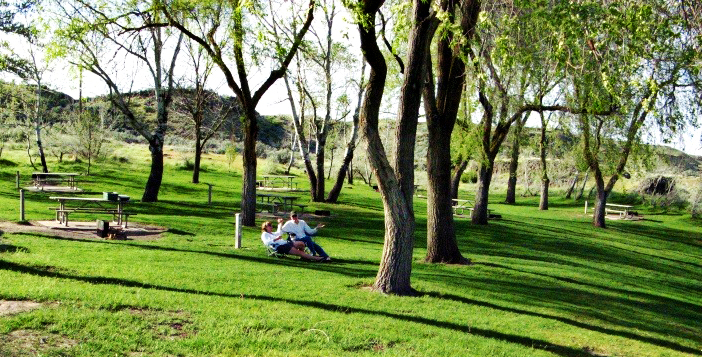

Palouse Falls Campground (Courtesy LugNutLife)

one is in the heart of land once carved and gnawed by massive walls of water, yet today one is lulled to sleep by the gentle sussuration of insects and the subdued the roar of the falls. There are excellent photographic opportunities available from the viewpoint, as well as a number of hiking trails toward the head of the falls and nearby rapids on the Palouse

Palouse Falls, 6×9 cm 1950 Baby Crown Graphic with 65 mm Schneider Angulon, XP-2 at f/16. View from visitor’s center outlook.

River. The breadth of the canyon and falls lends itself perfectly to modern panoramic digital photography (see iPhone panorama above) or ultrawide angle lenses, but less expansive yet impressive images can be obtained with modest wide-angle or “normal” lenses on classic cameras:

Palouse Canyon Looking Southward, Voigtlander Avus with 105 mm Skopar Lens, Kodak VC-160

The canyon south of the falls is bounded by private land, and requires special permission to explore (see Foster, T.). One half mile northwest of the campsite, reachable by small dirt tracks running west from the camp access road approximately one-half mile north of the park, is a miniature badlands. Time your trip to coincide with the full moon; a moonlit hike through this area is an eerie and unforgettable experience.

The canyon and falls are by spectacular by themselves, but the surrounding landscape offers a palette of flood-altered contours, from rolling virgin grassland dotted with wildflowers to teardrop-shaped, flow-contoured hills, and multiple nearby coulees and canyons. One of the closest of these is HU Ranch Coulee, formed when the wall of water rushing down Washtucna Coulee to the north overwhelmed its banks, turning south and ripping HU Ranch Coulee and Palouse Canyon out of faults in the underlying basalt. The ranch was stunning and while we were there, we found some Ranch land for sale. After all, who wouldn’t want to own a ranch in the USA? It’s always been a dream of mine!

Afternoon light, HU Ranch Coulee, just north of Palouse Falls (Digital Image)

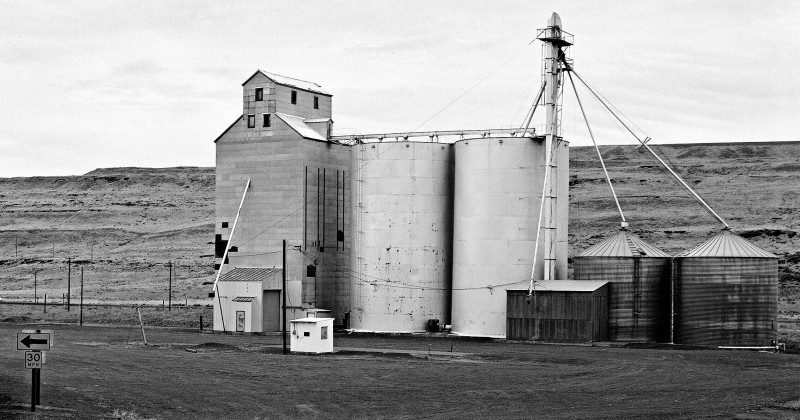

The rolling farmlands, colours, and wonderful light of the Palouse lie just north of Palouse Falls. From the park entrance, turn right and head northwest up the narrow, twisty contours of Highway 261. In a few miles, turn right onto highway 260/261 toward Washtucna after you stop and snap a picture of the grain elevator at the junction:

Grain Elevators, Highway 261. Ensign 820, Ilford XP-2.

From Washtucna, start your exploration of the Palouse by heading east along Highway 26 toward Colfax. From Colfax, turning northward on Highway 195 leads to Steptoe Butte, an ancient quartzite island jutting out of the Columbia lava flows, and one of the main  attractions of the Palouse. One of the few significant elevations in this area, Steptoe Butte is the site from which the most striking panoramas of this area are taken. Turning south on Highway 195 leads to the college town of Pullman, home of Washington State University.

attractions of the Palouse. One of the few significant elevations in this area, Steptoe Butte is the site from which the most striking panoramas of this area are taken. Turning south on Highway 195 leads to the college town of Pullman, home of Washington State University.

Steptoe Butte (courtesy geocaching.com)

The country south of the Palouse farmlands also yields valuable images. Rather than heading north to Washtucna, from the Palouse Falls park access drive south on route 261 toward the little town of Starbuck. The highway winds down through eroded hills into the Snake River canyon, with its spectacular Lyons Ferry railroad bridge (also known as the

Lyons Ferry Railroad Bridge (wide angle digital image, black and white conversion from colour original, Canon 18-55mm, equivalent to ~28mm on 35mm camera)

Joso Trestle). The bridge, built in 1912, was at its completion the longest and tallest railway bridge in the world and is worth more than a casual snapshot. Although the views of its 240 foot pillars and 3920 foot span leaping the river’s valley cry out for a wide angle lens, dramatic views can be taken even with the more limited angle of a “normal” classic camera lens.

Lyons Ferry railroad bridge, Voigtlander Bessa, Skopar lens

Returning to the campsite, the Rawhide Grill’s sign was the only sign of humanity in miles of rugged, flood-ravaged hills and gullies:

For an exceptional view of the Palouse and the canyons, watch this video taken from an ultralight trike as it soars down the Palouse River (be sure to watch in Full Screen mode):

THE VALUE OF WANDERING:

Most importantly, remember that the key to fully experiencing the Palouse (and finding unique images) is that destinations are not important. On two expeditions to the Palouse, I have set out for Steptoe Butte three times. I have never reached Steptoe Butte, and I do not have not a single image taken from this spectacular viewpoint. On each day’s outing, I have been seduced by the line of a furrow, distracted by a shadow sliding down a valley, lured by a glimpse of a barn, or sidetracked by one of the dozens of little roads winding off Highway 26. Experience the Palouse by getting lost. Wander. Pick a road at random and explore it. Wandering this way has led me to afternoon shadows, abandoned farms, field lines arcing up rolling hills, and fascinating shadows. There are images over every rise, and undiscovered pictures around every bend:

(All digital images)

WATCHING FOR DETAILS:

The majority of published Palouse images focus on broad vistas of magnificent scenery, yet this area is rich with rustic small details. Pause in small towns like Washtucna, a small farming hamlet with a pub, a modest number of houses, and an air of neglect. Do not hurry through these small, 1960s-style towns in your hurry to find the real “photo opportunities.” Stop. Look in back streets, examine abandoned stores and gas stations, muse over doors and knockers and peeling paint. Stand in the middle of Main Street and look at the view down the white line.

Wandering the sidewalks of Washtucna revealed this abandoned store, with peeling paint and a back room filled with shadowy objects dimly visible through the dusty windows:

“Sidewalk Closed”, Washtucna. Voigtlander Bessa, VC-160

Farther down the street, an old Ford truck partnered a weathered gas station:

Exploring farther afield turned up an abandoned barn on Highway 26. Wandering around brought me next to the side door, held closed with chains and a bar:

Looking closer at barns, I found this hinge against faded red paint on weathered wood:

Throughout the Palouse, there are thousands of details like this, just waiting for someone with a careful eye to discover them. Remember also the the Palouse is not just about fields and farmhouses. There are miles upon miles of prairie and grassland that abound with flowers in the spring and early summer:

Silky Lupine

And remember always that the key to photography is seeing. Learn to look, and when you look, try to see. Sometimes you need to come back to the same site several times before you really see it. Enjoy the vistas, but look at your feet. See the flowers and the grasses. Follow an ant. If you climb over a rock, look at the rock. I did, and discovered a palette of colourful lichen:

ARTS IN THE PALOUSE:

At the risk of sounding like a travel brochure, it is only fair to include the Palouse’s cultural life – this area is more than barns and fields and canyons. With three nearby major universities (Washington State University, the University of Idaho, and Gonzaga University) plus a wealth of local and regional artists, art, music, theater, and dance flourish. The Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival in Moscow is the largest educational jazz festival in the world. The Dahmen Barn in Uniontown provides studio space for artists and is a major teaching center as well as a prime photographic subject. Visit the web site of Alison Meyer, one of the area’s best-known photographers, for tips on photographing the Palouse. The first Palouse Fiber Arts Festival was held in 2014. Farmer’s markets, renaissance fairs, concerts, and even a Lentil Festival fill the spring to autumn months.

OVERFLOWING WITH IMAGES:

I would recommend the Palouse to anyone with an eye for images. Rarely have I found a region with this degree of photographic abundance. The dry climate preserves old wooden structures, and encourages vistas populated only by grassland and sagebrush. The builders of the California megahouses and overpriced ski retreats that dot previously-remote areas have not yet discovered this quiet corner of the continent. Virtually unknown to the general public, this unspoiled area is almost tourist-free.

Rand at Palouse Falls, June, 2013

REFERENCES:

Baker, V. “Joseph Thomas Pardee and the Spokane Flood Controversy.” GSA Today v.5. no. 9, September 1995. http://gsahist.org/gsat2/pardee.htm

Barlow, C. Lake Missoula/Scablands/Columbia Flood. http://www.thegreatstory.org/scablands.html

Bjornstad, B. “Erratic Behavior.” http://www.brucebjornstad.com/#!erratic-behavior/c66t

Bretz, J Harlen. “The Channeled Scabland of the Columbia Plateau”. Journal of Geology 31: 617–649 (1923)

Foster, T. “Discover the Ice Age Floods.” http://hugefloods.com/

Foster, T. Palouse Falls and Palouse River Canyon – Whitman County Side.’ http://iceagefloods.blogspot.ca/2009/10/palouse-falls-and-palouse-river-canyon.html

Glaciers of the American West Web Site. “J. Harlen Bretz.” http://glaciers.us/jhbretz

History Link.org. “Bretz, J. Harlen (1882-1981), Geologist. http://www.historylink.org/_content/printer_friendly/pf_output.cfm?file_id=8382

Idaho Public Television. “A Palouse Paradise.” http://idahoptv.org/outdoors/shows/palouseparadise/palouse.cfm

Lee, Keenan. “Catastrophic Flood Features at Camas Prairie, Montana.” Inside Mines Web Site. http://inside.mines.edu/UserFiles/File/Geology/Camas_red.pdf

Museum of the City. “Great Missoula Floods.” http://www.museumofthecity.org/the-great-missoula-floods/

Northwest Geological Society. “Ice Age Floods Through the Western Channeled Scablands.” http://www.nwgs.org/field_trip_guides/ice_age_floods.pdf

Royal Geographical Society. “Hidden Journeys. DENVER TO SEATTLE – The Palouse at 13,000m:A Patchwork Sea.” http://www.hiddenjourneys.co.uk/Denver-Seattle/Palouse/Highest/hjp.PAL.NASA.001.aspx?mode=image

Soennichsen, J. Bretz’s Flood: The Remarkable Story of a Rebel Geologist and the World’s Greatest Flood. Sasquatch Books, seattle, 2008

Soennichsen, J. Washington’s Channeled Scablands Guide: Explore and Recreate Along the ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail. Mountaineers Books, Seattle. 2012.

Soennichsen, J. “Legacy: J. Harlan Bretz (1882-1981). A Scablands Geologist Whose Theory Finally Won Out.” University of Chicago magazine, Nov-Dec, 2009. http://magazine.uchicago.edu/0912/features/legacy.shtml

Suckow, L. “Hills, Grain Elevator, and Little Yellow Plane.” https://www.flickr.com/photos/walla2chick/178199167/

U. S. Geological Survey. “The Carving of the Scablands.” http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/geology/publications/inf/72-2/sec5.htm

Washington Trails Association. “Palouse Falls.” http://www.wta.org/signpost/go-hiking/hikes/palouse-falls

Weis, Paul L.; Newman, William L. (1976). The Channeled Scablands of Eastern Washington: The Geologic Story of the Spokane Flood.

U.S. Geological Survey. “The Channeled Scablands of Eastern Washington” Articles. “The Carving of the Channeled Scablands.” http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/geology/publications/inf/72-2/

Wikipedia. “Channeled Scablands.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Channeled_Scablands

Wikipedia. “Dry Falls.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dry_Falls

Wikipedia. “J. Harlen Bretz.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J_Harlen_Bretz

Wikipedia. “Loess.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loess

Wikipedia. Missoula Floods.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missoula_Floods

Witmer, S. “Palouse Loess.” http://epod.usra.edu/blog/2010/08/palouse-loess.html