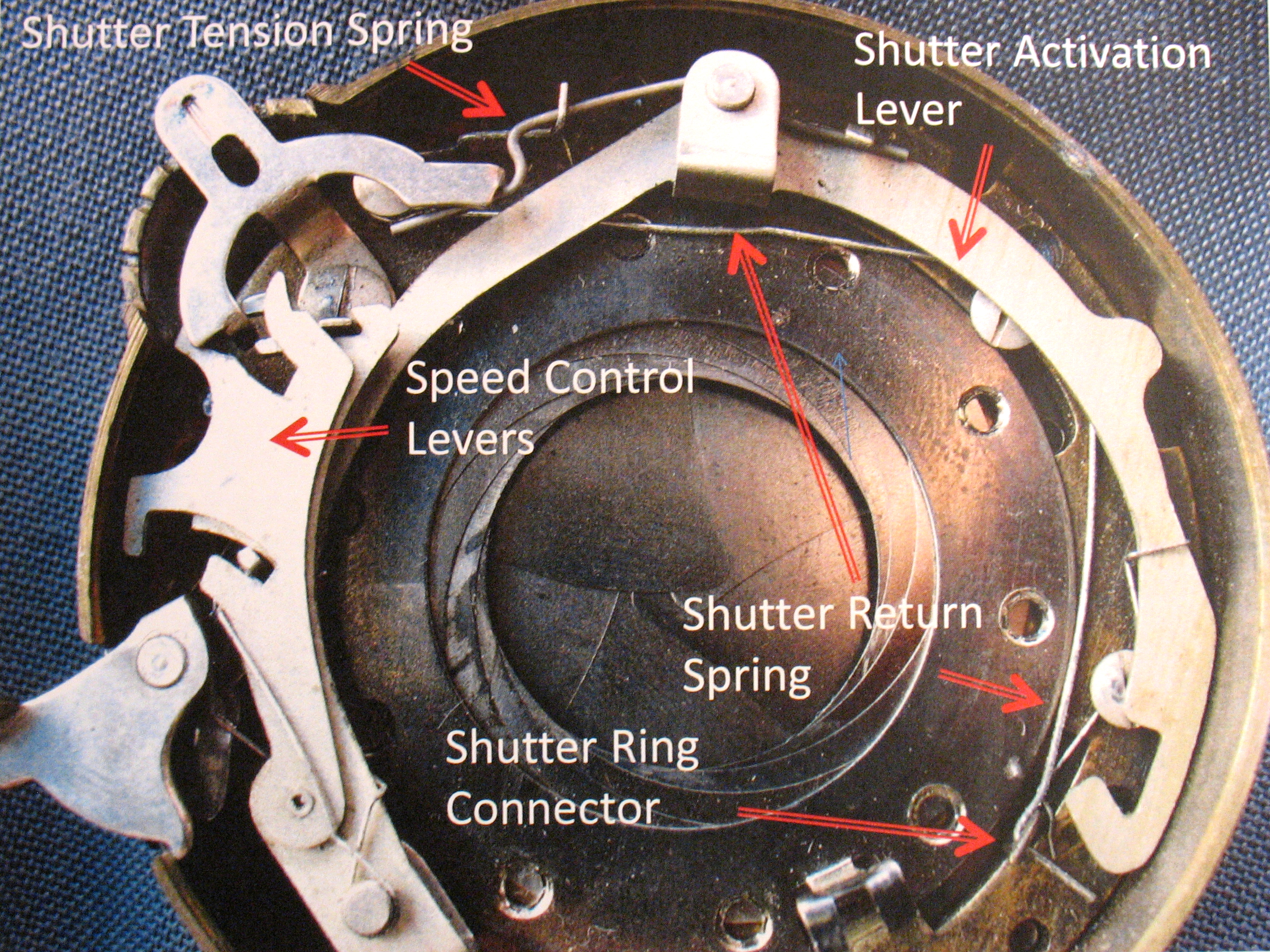

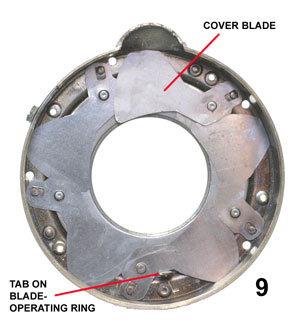

Compur Leaf Shutter Mechanism

This article introduces the topic of classic camera shutters. Subsequent postings will explore in more detail the protean topic of clockwork leaf shutters, followed by discussions of pneumatic shutters and the various types of classic curtain shutters.

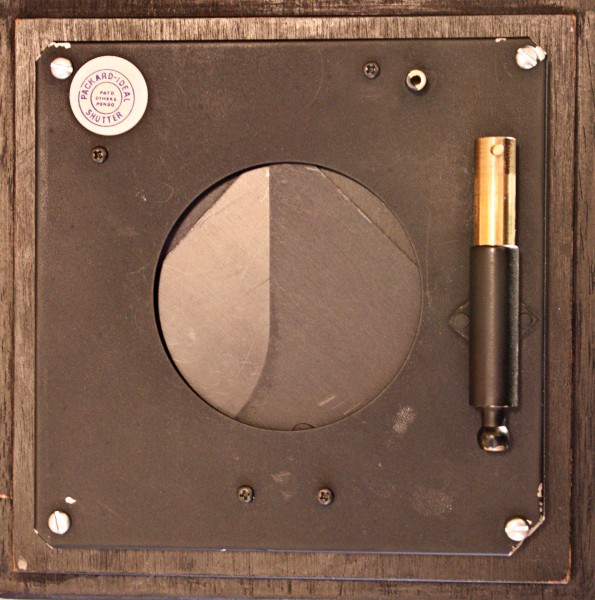

Lens With Guillotine Shutter

There are two ways of controlling the amount light used in exposing a glass plate or sheet of photographic film: the area of the lens opening, known as the aperture or f-stop, and the length of the exposure. In the early days, when plates were wet and emulsions were deadly slow, life was simple – the photographer merely removed his hat, placed it over the lens, removed the dark slide, and then uncovered the lens for the desired number of seconds.

As emulsions increased in speed, life became more complicated, and the need arose for a mechanical device to control short exposures. The first known shutter, a “drop” or “guillotine” shutter consisting of a board with a hole in it moving past the lens opening, was used in1845 by the French physicists Fizeau and Foucault for photographing the sun. A similar shutter was used by Matthew Brady, the great civil war photographer, in 1850.

Shutters became more common between 1850 and 1880, but slow emulsions made them more of a handy accessory than a necessity. Many shutters consisted of pivoted lens covers or

Guerry Flap Shutter, c. 1881

Early Pivot Shutter (EP)

variations on the simple flap. After 1880, the advent of hand-held cameras and the development of faster films increased the need for a way of controlling short exposure times and led to a period of rapid technological advancement. By 1890, the early forms of all of the common shutters used in the 20th century had been developed.

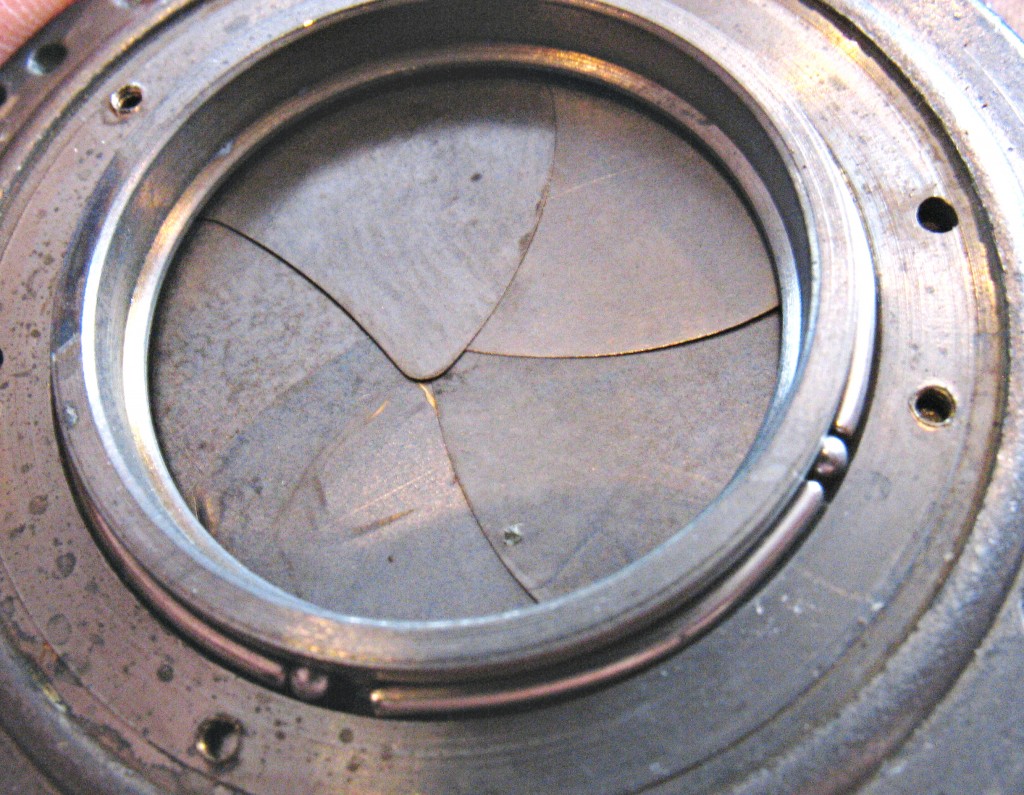

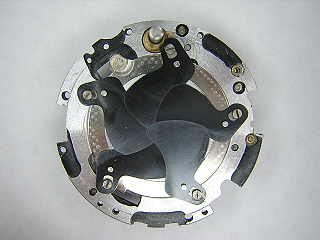

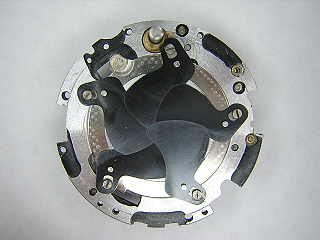

Overall, shutters fall into three main categories: Rotary or “sector” shutters, leaf shutters, and curtain-type shutters. In their simplest form, sector shutters may be considered to represent a rotary version of the guillotine or drop shutter, consisting of a pivoting metal plate with a round or kidney-shaped opening exposing the lens as it rotates. Leaf shutters, also now frequently called “between the lens shutters”, consist of a set of blades that rotate to uncover the lens opening.

Five-Bladed Prontor SVS Leaf Shutter

Early versions were air-driven, while the majority of later models were spring-driven with a pneumatic or clockwork timing mechanism. Curtain-type shutters may be divided into focal plane shutters, situated next to the film plane and used until the 1990s on millions of 35mm cameras and the famous Speed Graphic large format cameras, and “Rouleau” or roller blind shutters, situated behind or in front of the lens and represented by the highly successful Thorton-Pickard shutters common before 1915.

Thornton-Pickard Royal Ruby Triple Extension Camera with Roller Blind Shutter

Common to all three types is the need for an accurate and reproducible timing mechanism. Until the 1880s, shutter timing was very crude, depending on the tension of a spring or rubber band or the retarding effect of a leather brake. The rubber band-powered Lancaster Rotary shutter from 1885, frequently found on Instantograph cameras, is an

Lancaster Rotary Shutter (EP)

example of this type of shutter. The first major advance in shutter timing occurred in 1886, when Arthur S. Newman developed a shutter with a pneumatic cylinder retarding mechanism, thus introducing a new era in shutter accuracy and setting the stage for the dominance of pneumatic shutter timing for the next quarter century. This was followed in the early twentieth century by clockwork time delay systems, and finally, in the late twentieth century, by electronic timers.

In the late 1800s, a variety of sector shutters were in use. While many, like the Lancaster shutter, were of simple design, some, like the Newman and Guardia of 1895, were complex

Newman and Guardia Sector Shutter (EP)

devices with pneumatic timing that were capable of a number of speeds from 1/2 to 1/100 second. Unfortunately, these sophisticated models were abandoned in favor of leaf and curtain shutters, and the sector shutter was relegated to the cheapest form of photographic technology, the box camera. However, in this role, the sector shutter found its true home, and millions of

Kodak Rotary Sector Shutter, 1896 Pocket Kodak (EP)

these cheap and durable devices were produced for the consumer market by Eastman Kodak and other manufacturers well into the 1960s.

The first leaf shutter was probably constructed by Mann in 1862. Another early model with only two blades, the Sands’ Patent Shutter, was designed by C. Sands of Sands, Hunter and Company

American Optical Acme Tailboard Camera with Sands and Hunter Shutter, 1885 (EP)

in 1881. A major milestone in shutter development and manufacture occurred in 1890 when Bausch & Lomb, one of the most famous of the early Rochester optical and camera companies,

Bausch and Lomb Iris Diaphragm Shutter

entered the shutter business in 1890 with their pneumatic “Iris Diaphragm” shutter. This was a “self-diaphragming” shutter, a precursor to the modern shutter with its separate aperture and shutter blades, in which one set of blades opened to a preset aperture, then closed at the the end of the exposure. Later B&L pneumatic shutters such as the Victor had both shutter blades and an iris diaphragm.

1904 Bausch and Lomb Catalog

Like many technological advances, the concept of the pneumatically-timed shutter sprouted in more than one site; in the same year, Voigtlander independently introduced in Germany the four-bladed “Verschluss” pneumatic shutter (see Reiss’ site on Compur shutters).

Bausch and Lomb was, and still is, one of the main pillars of the American optical industry. Yet in the story of the pneumatic shutter, it was as important for those who left the company as it was for its own accomplishments. In 1878, Ernst Gundlach, reputed to be a difficult individual, left the company and eventually founded the Gundlach Optical Company. In its several manifestations with and without Ernst Gundlach this company manufactured the well-known Gundlach cameras, together with shutters, and other optical equipment until 1972. In 1899, Andrew Wollensak, who designed the Iris Diaphragm and other shutters, left Bausch and Lomb and founded the Wollensak Optical Company, manufacturing a line of high quality, reasonably-priced shutters.

Optimo Pneumatic Shutter

The famous pneumatic “Optimo” shutter was designed by Wollensak in 1909 and was sold extensively until 1930. It was joined by the popular Betax, Alphax, and Rapax shutters. Production of lenses began in 1902, with production in subsequent years of shutters and lenses for all of the major camera manufacturers. The Wollensak lens and shutter catalog from 1919 is worth reviewing both as art in its own sake and as a piece of

Wollensak Lenses and Shutters Catalog 1919

history with fascinating images of the time. The company existed in various forms through the war years, manufacturing such well-known items as the Optar lenses and Graphex shutters for the Graphic press cameras, until it finally closed its doors in 1972.

One fascinating historical tidbit is that the Wollensak factory stood abandoned and essentially undisturbed, an undiscovered time

Equipment in the Abandoned Wollensak Factory

capsule, until 2007, when the building was put up for sale. At that time, an explorer from the Urban Landscape entered the building, found it virtually untouched since the day the last employee left,

Wollensak Factory Stairs

photographed its interior, and posted his photographs on the Internet. They can be viewed at The Urban Exploration Forum site. The entire building and its contents finally sold for $85,000.

Unfortunately, the maximum accurate speed of a purely pneumatic shutter is limited to 1/100 sec or less. Later models, such as the Optimo and Koilos, achieved a greater range with a combination of pneumatic regulation for slow speeds and spring-driven timing for faster speeds. However, the advent of faster films with their requirement for very fast shutter speeds, together with the development of a simpler alternative, doomed the pneumatically braked shutter.

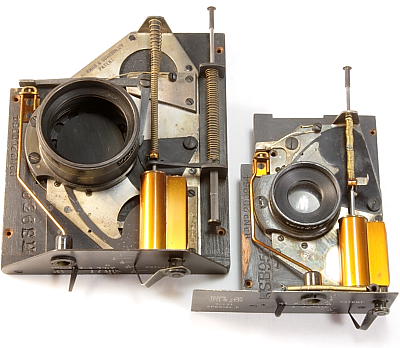

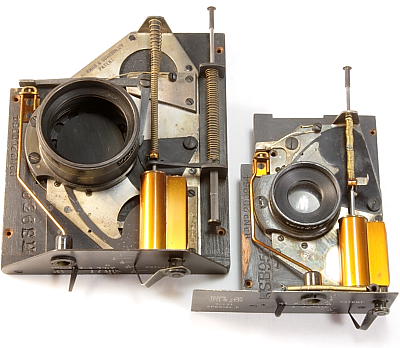

This advance was to come from a third offshoot of Bausch and Lomb: Ilex. In 1910, two Bausch and Lomb shutter designers, Rudolph Klein and Theodor Brueck (Brueck had designed the “Volute” shutter in 1902), invented a revolutionary shutter delay mechanism, involving a rotating gear and a rocking pallet (U.S. Pat. 1,092,110). This mechanism, similar to that used for regulating clocks, made possible a compact mechanism allowing a shutter’s slow speeds to be accurate independent of temperature and atmospheric conditions. The original patent is reproduced in its entirety in the post “Shutters – A Landmark Patent!”.

Klein and Brueck left Bausch and Lomb and set up their own business, initially called the “XL Manufacturing Company”, to manufacture the new shutter. However, they soon discovered that C. P. Goerz was also making a line named the “X excel L” shutters, so to avoid confusion they renamed their shutter the “Ilex,” and in 1911 renamed their firm the “Ilex Manufacturing Company” and later the “Ilex Optical Company”. Shortly thereafter, Friedrich Deckel of Munich bought the rights to use their delay mechanism on a royalty basis in his famous line of Compur shutters. Ilex had one other major contribution to twentieth-century photography: the invention of the self-contained internal flash synchronization mechanism during World War II.

Ilex Paragon 215/355 mm f/4.8 Convertible Lens in Ilex Shutter

In addition to shutters, Ilex produced many quality lenses under the Paragon name. Ilex lenses and shutters were sold and used in large numbers until well after World War II, and are readily available on the used market today.

The invention of a slow-speed braking system that was compact, durable, and accurate under all conditions was a springboard for shutter development for the next half century. Prior to Klein and Brueck’s invention of the clockwork slow-speed escapement, non-pneumatic, variable-speed shutters for handheld cameras had been around for a number of years, the most notable being the indestructible Kodak Ball-Bearing Shutter. However, these either lacked slow speeds, depending on varying spring tension to vary shutter speeds and, like the Kodak, being restricted to speeds faster than 1/25 second, or depending on a variety of exotic braking systems to regulate slow speed exposures. Valentin

Linhof Shutter, Early 1900s (EP)

Linhof, manufacturer of the famed Linhof technical cameras, actually launched his career as a shutter manufacturer, with his first models of 1887 using a leather brake to control slow speeds. Later, Kenngott used a similar mechanism in the first Koilos shutters. In fact, a leather brake was in use as late as 1902 in Steinheil’s “Universal Automatic Shutter Model C”, designed by Christian Bruns. Klein and Brueck’s compact device changed the direction of photographic innovation.

After Ilex sold the rights to the clockwork slow-speed escapement, the spotlight on shutter development shifted to Germany. One of the giants of the German optical industry in the late 19th century was the firm of C. A. Steinheil, a major manufacturer of astronomical and optical equipment as well as photographic lenses and shutters. Both Friedrich Deckel and Christian Bruns were employed by Steinheil. Deckel left to found his own establishment in 1898, and was joined by Bruns in 1903; the resulting company was eventually named F. Deckel. Their cooperation produced in 1905 the famous Compound pneumatic shutter. This was the longest-lived of the pneumatic shutters, being

Compound Shutter with Zeiss Protar

produced continuously until 1970. It longevity can be attributed to its large size and dependability; some of the these shutters are still in use today, being the best choice for the largest of classic large format lenses.

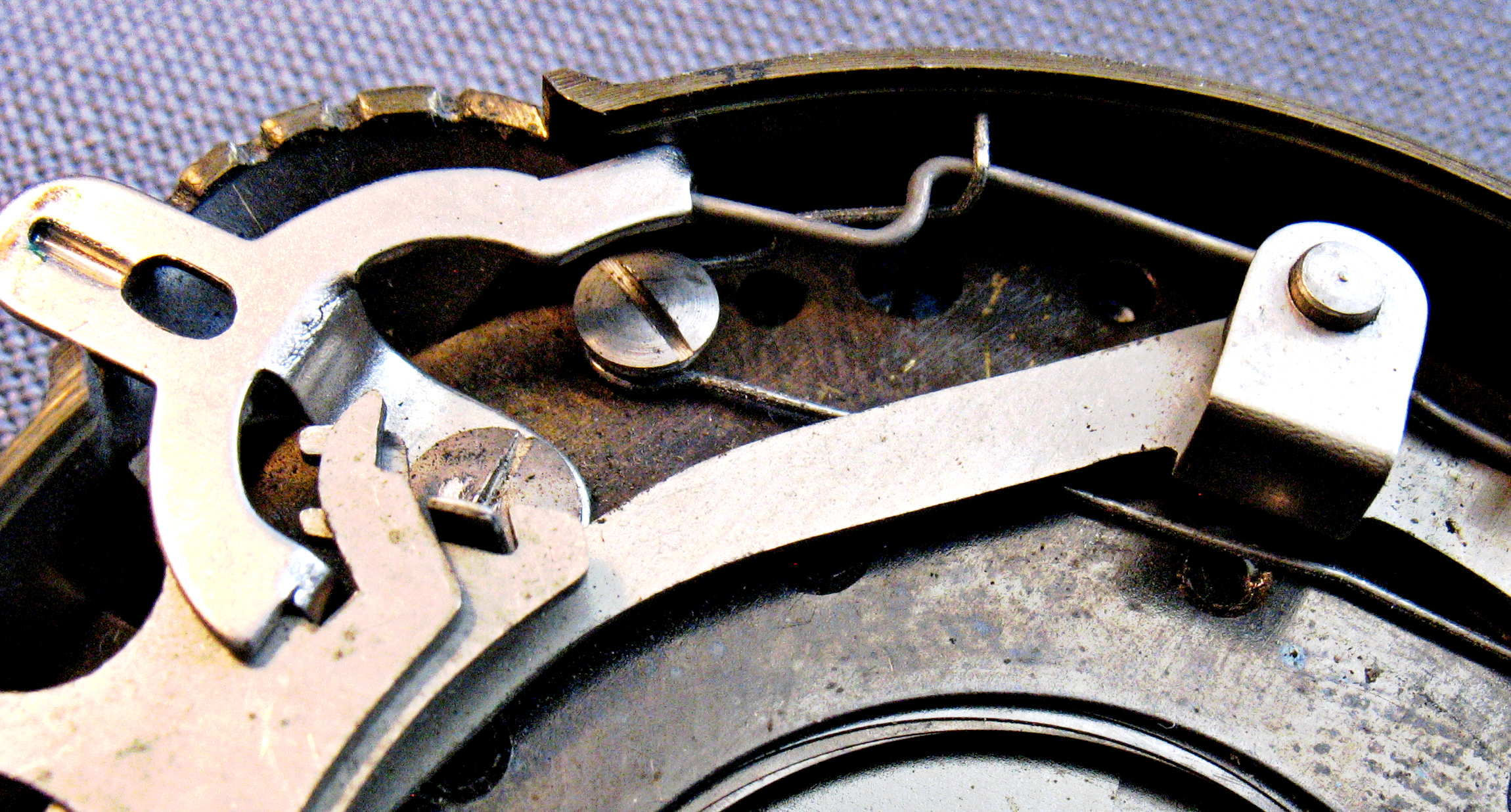

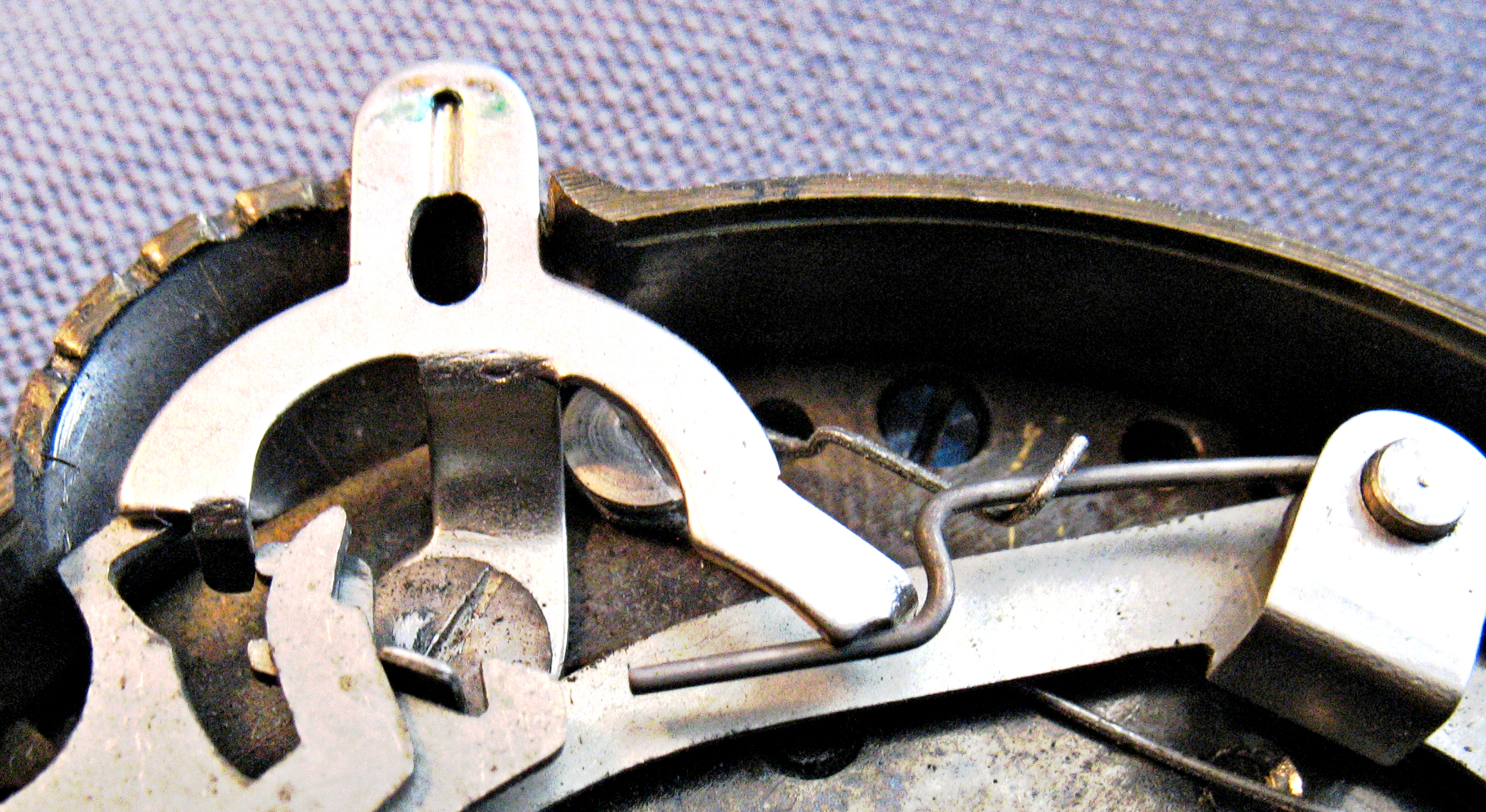

After receiving rights to Ilex’s design, Friedrich Deckel wasted no time in putting the slow-speed delay escapement into production, and the first of the famous Compur shutters appeared in 1912. It is interesting to note that the Compur was not actually a new shutter, but rather a modification of the Compound. In designing the Compur shutter, Deckel apparently took the Compound shutter and replaced the pneumatic cylinder with Klein and Brueck’s clockwork slow speed escapement, thus simplifying and expediting the new design. The name “Compur” reflects this genesis from the Compound shutter, being a fusion of “Compound” and “Uhrwerk”, the German word for “clockwork” (see Reiss). Consequently, the Compur is actually a “Clockwork Compound” shutter.

It should be noted that the actual relationship between Deckel, Bruns and the development of the Compur shutter is somewhat murky; Bruns stayed with Deckel for only a short time, but continued to work on shutter design after severing his legal relationship with him. The majority of the design work was done not by Deckel, but by Bruns. Carl Zeiss owned a portion of F. Deckel and may have obtained the Compur patent from Bruns in order to share it with Deckel. Zeiss also quietly owned stock in the German Gauthier shutter factory and in Bausch and Lomb, and may have facilitated use of this design by both companies (see Reiss). Zeiss was in turn obligated to use Compur shutters in the majority of their cameras.

The original Compur shutters were set by a dial at the top of the

Compur "Dial-Set" Shutter (Note resemblance to Compound shutter)

shutter and have become known as “Dial-Set Compurs”, as opposed to the more familiar “Rim-Set Compurs”, introduced in 1927, with their speeds set by rotating an outer ring.

Compur Shutter, Rim-Set Type

Independent of Deckel and the Compound/Compur branch of the evolutionary tree, the brothers Alfred and Gustav Gauthier established a shutter factory at Calmbach in the Black Forest region of southwestern Germany in 1902 This produced the the well-known pneumatic Koilos shutter, followed by a long line of less expensive leaf shutters that were, by agreement with Zeiss, mostly equipped with fewer speeds and destined for cheaper cameras. However, the Gauthier factory did produce one professional-quality shutter, the Prontor, in 1935. This became Gauthier’s star product, with a daily production of 10,000 Prontor shutters by 1960.

Until the patents on the Compur and the clockwork slow speed escapement expired, Germany largely controlled shutter production. Part of the impetus for the development of American shutters such as the the Kodak Supermatic was an effort to find an alternative to the monopoly held by German manufacturers such as Deckel, and Gauthier.

By the late 1950s, the majority of photography was done with 35mm cameras, and Zeiss and other German camera manufacturers were riding a tide of success based on the concept of a small, eye level camera with an interlens leaf shutter and interchangeable front lens elements. These were of excellent quality, but expensive to produce and mechanically complicated. Because of the leaf shutter mechanism surrounding the lens opening, the maximum aperture of the lens was limited. Starting in 1953 with Zeiss’ Contaflex, a number of single lens reflex cameras with leaf

Zeiss Contaflex S

shutters were developed, including the Retina Reflex, the Voigtlander Bessamatic, and the Wirgen Edixa (1962). However, these required coordination of a flip-up mirror, the leaf shutter, and a focal-plane baffle plate, making the mechanism complex.

Caught up in their success, German manufacturers ignored the growing popularity of the simpler and less expensive Japanese designs based on interchangeable, high quality lenses of large aperture combined with focal plane shutters. The collapse of the German camera industry was inevitable, and during the 1960s and 1970s, Zeiss and the majority of the other German manufacturers ceased production. The effect on the leaf shutter industry was predictable, and by the the mid 1970s, production at Deckel and Gauthier was a mere trickle, primarily devoted to Hasselblad and large format lenses. Ironically, the East German camera manufacturers, based in Dresden, embraced the Japanese concept and achieved excellent success with the Exakta and Practika lines based on focal plane shutters and interchangeable lenses. The East German camera industry collapsed not because of lack of vision, but because of the collapse of the Soviet-type German Democratic Republic in 1989.

The best known of the curtain shutters is the focal plane shutter, consisting of a moving curtain with a transverse slit that moves across immediately in front of the film, exposing it in a sequential fashion. The first known use of a focal plane shutter is thought to be by the famous English photographer William England in 1861, whose camera employed a drop shutter with adjustable slit width located at the focal plane. He is therefore credited with the invention of this type of shutter.

There are two ways of controlling the exposure using a focal plane shutter: curtain speed and slit width. Early curtain shutters, both behind the lens and focal plane, used a combination of both methods. The typical early focal plane shutter consisted of a rubberized fabric curtain driven by a clockwork mechanism. Increasing the tension in the driving spring drove the curtain faster, thus effectively increasing shutter speed; however, top speeds were limited by the strength of the curtain material. Slit width was adjusted by using two half-curtains linked by chains or tapes that allowed the spacing between the curtains to be adjusted. In early shutters, changing the curtain spacing meant opening the camera to manually adjust the shutter mechanism; later models used tapes that could be adjusted from outside the camera.

Functional focal plane shutters reminiscent of those used on modern film cameras came on the market around 1890. Thornton-Pickard marketed a focal plane shutter in 1891 in addition

Thornton-Pickard Focal Plane Shutters (EP)

to their behind-the-lens shutters; this was produced in improved versions into the early part of the 20th century. As early as 1902,

Newman and Guardia Focal plane Shutter 1902 (EP)

Newman and Guardia created a two-blind focal plane shutter whose shutter speed varied by controlling slit width and which achieved speeds of 1/10 – 1/800 second.

In 1925, Leitz, manufacturer of the Leica, introduced the dual-curtain focal plane shutter. This was a major technological breakthrough, eliminating precut slits and the need for adjustable spring tension. The slit is formed by opening the first curtain; as it opens, it is followed by the second curtain after a delay timed by a clockwork escapement mechanism. The curtains move at a single, predetermined speed across the film. Faster shutter speeds are provided by changing the delay between the opening of the first curtain and the closing of the second, thus effectively varying the slit width Dual curtain focal plane shutters are also self-capping, as the curtains are designed to overlap as the shutter is cocked to prevent double exposure. This mechanism formed the basis for the focal plane shutters in most 35mm single lens reflex cameras until the advent of lightweight metal vertical blinds in the 1980s.

The evolution and mechanism of focal plane shutters has been carefully and extensively described on the Early Photography web site at http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/shutterm.html.

Each shutter type has its advantages and disadvantages. Leaf shutters can synchronize with most flashes at any speed, and tend to be quieter and more compact than focal plane shutters. However, unlike focal plane shutters, their mechanical complexity typically limits them to speeds of 1/500 sec. or less. Having interchangeable lenses necessitates a shutter in each lens, like the Hasselblad 500, a behind the lens shutter, like the Paxette, or lens arrangements where only the front half of the lens can be exchanged, like the many German rangefinder cameras of the 1960s. Today, between-lens leaf shutters’ one remaining stronghold is in large format photography.

Focal plane shutters, mounted immediately in front of the film plane, readily allow for interchangeable lenses and are capable of very fast shutter speeds. However, they are noisy, less durable than well-crafted leaf shutters, and, when combined with the bounce of a reflex mirror flipping upward, cause a significant degree of camera shake. In addition, the progressive movement of the curtain slit across the film results in distortion of the shape of a fast-moving object, which is actually in a different position as the curtain exposes different parts of the film. Modern designs, with vertically-traveling lightweight shutter blades, have partially remedied these problems. Finally, care must be taken not to leave cameras with focal plane shutters uncovered in the sun, as the sun’s image focused on the curtain can actually burn holes in the curtain.

Note:

Some of the historical data on shutter development is covered in more detail in Rudolf Kingslake’s excellent article on the Rochester, NY camera companies. Many superb photographs of early shutters and vintage cameras can be viewed on the “Early Photography” web site and on Wagner Lungov’s site. The Early Photography site is one of the best on the internet and has excellent discussions of shutter mechanics and function. Images from this site are designated (EP). Special thanks are in order to both of these authors for use of images of antique shutters. Klaus-Eckhard Reiss’ web site is a rich and insightful analysis on the development of the Compur shutter and the demise of the German camera industry.

For aficionados of vintage cameras, one site that must not be missed is David Tristram Ludwig’s “Antique Cameras” collection (http://www.dtristramludwig.com). David’s collection is one of the finest in the world, and his photographic images are excellent. David was kind enough to allow me to use his images of the American Optical camera with the Sands Hunter Shutter and the Bausch and Lomb 1891 Diaphragm Shutter (after he had reminded me tartly that I forgotten to cite him – I do get it right most of the time!).

This article provides a survey of the development of the photographic shutter. Pneumatic shutters, clockwork leaf shutters, and curtain shutters will be described in more detail in subsequent postings.

References:

Cosens, Robert. “Photographers of Great Britain and Ireland 1840 – 1940: William England.” http://www.cartedevisite.co.uk/photographers-category/biographies/england-william/.

“Diaphragm or Leaf Shutter.” Living Image Camera Museum article. http://licm.org.uk/livingImage/Shutters-Leaf.html

“Early Photography.” http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/index.html.

“Exposure.” Wikipedia Article. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exposure_%28photography%29.

Kingslake, Rudolf. “A History of the Rochester, NY Camera and Lens Companies.” http://www.nwmangum.com/Kodak/Rochester.html#Ilex.

“Leaf Shutter.” Camerapedia article. http://www.camerapedia.org/wiki/Leaf_shutter

Ludwig, David Tristram. “Antique Cameras.” http://www.dtristramludwig.com.

Lungov, Wagner. “Photographs of my Family and Other Adventures.” http://www.lungov.com/wagner/index.html.

Purdum, Ernest. Online posting for Large Format Photography Forum. 2006. http://www.largeformatphotography.info/shutters-history-and-use.html.

Reiss, Klaus-Eckhard. “Up and Down with Compur: The Development and Photo-Historical Meaning of Leaf Shutters.” http://www.kl-riess.dk/compur.eng.html.

“Reprinted Company Catalogs.” Craig Camera Web Page. http://www.daguerreotype.com/lit_catalogreprints.htm.

Urban Exploration Forum. “Wollensak, the Time capsule.” http://www.uer.ca/forum_showthread_archive.asp?fid=14&threadid=44384.

Wikipedia article. “Focal Plane Shutters.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Focal-plane_shutter.

“Wollensak Lenses and Shutter Catalog, 1919.” http://www.cameraeccentric.com/html/info/wollensak_13.html.