A number of cameras manufactured between 1910 and 1950 are eminently suitable for high-quality fine art photography, while many more are, for one reason or other, best left as bookshelf decorations. Photography lovers are fascinated by classic cameras and how they used to function, in fact, there are blog posts such as https://www.hooliganrocknroll.com/a-snapshot-of-3-cameras-from-the-past/ that can provide a quick overview of what they started out as to what we have now.

The first consideration is film size. Over the last 100 years, Kodak has produced roll film in a multiplicity of formats from the tiny disc and 110 sizes through 35mm up to 7×5 inch “Postcard” widths (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_format). Over the years, the majority of these formats have been eliminated, and roll film is presently available primarily in 35mm and 120 sizes, together with 4×5, 5×7, and 8×10 sheet film. Consequently, many cameras from 1910-1930 are unusable without modification because film is no longer available. Fortunately, 120 film was in use as early as 1901, and many fine cameras are available that use this film size. Although 35mm is also a common format in the vintage camera market, I have elected to work exclusively with medium format cameras using 120 film because of the higher image quality inherent in the larger negative. Despite the superb images possible with large format (4×5 and larger), I have avoided formats larger than 120 because of the difficulty and expense inherent in getting large format sheet film developed, scanned and printed. Consequently, all of my vintage photography is done with cameras using 120 roll film.

One thing you should be aware of: Kodak’s ill-fated (to my mind) experiment with 620 film. 620 is basically 120 film spooled onto a narrower spindle with smaller end flanges. Consequently, today’s 120 rolls are too big to fit into a camera designed for 620 film. Since a large proportion of Kodak’s cameras from 1932, when 620 was introduced, through the 1940s used 620 film, there are vast numbers of Kodak roll film cameras that cannot be used with off-the-shelf film. There are a number of ways in which 120 can be used in a 620 camera, including rerolling 120 film onto 620 spindles in total darkness, or trimming off the edges of the flanges on the 120 rolls (see Camerapedia’s entry on these workarounds at www.camerapedia.org/wiki/620_film), but to my mind, the nuisance factor is just too great, and my 620 Kodak cameras are gracing the ends of my bookshelves. Fortunately, European camera manufacturers never bought into the 620 concept, and all of the European medium format roll film cameras employed 120 film.

620, 120 Metal, 120 Plastic, and 120 Wood Film Spools

The second consideration is the lens type. A camera is a box with a lens on one end and film on the other. If either of the two is suboptimal, it’s not worth snapping the shutter. Many vintage lenses are of superb quality, and some, such as the Heliars and Ektars, are legendary. Others, such as the single-element meniscus lenses, are best avoided. Lenses will be discussed below and elsewhere in this blog.

My primary source for vintage cameras is eBay. A few dealers sell vintage cameras on line, but their prices are typically high. There are risks to buying vintage equipment on eBay, and one should be prepared to do some degree of cleaning and restorative work on most purchases. Restoration techniques will be discussed later. The buyer is strongly advised to peruse the seller’s pictures and descriptions carefully for signs of rust, worn bellows, and defective shutters. Do not be afraid to ask questions of the seller, and do not hesitate to send back a camera that is not as described. With luck, one may acquire a half-century old treasure that looks as if it was just taken off the shelf. However, even under the best of circumstances, one should be prepared to acquire a few cameras that are destined to spend their lives as bookends.

There are a number of excellent references on classic cameras. Many of these are listed in Camerapedia’s list of photographic references at http://www.camerapedia.org/wiki/Sources:_English_language#British_cameras. Naturally, the bible of classic camera aficionados is James and Joan Mc Keown’s wonderful tome McKeown’s Guide to Antique and Classic Cameras. This huge volume is much more than a price guide, being the one source where information on cameras of the last 150 years is summarized in one place.

The following is a summary of my thoughts regarding a number of models of vintage medium format cameras suitable for fine art work. The list is by no means all-inclusive, and there are a number of fine cameras with which I have only limited familiarity. The reader may find it useful to consult David Silver’s excellent article on classic roll film folding cameras on the International Photographic Historical Society’s web site at http://www.photographyhistory.com/cc2.html.

AGFA/ANSCO:

Agfa, founded in Berlin in 1867 as a manufacturer of photographic chemicals, most prominently the film developer Rodinal, produced cameras under its own name in Germany from 1925 until 1983. Folding 120 roll film

The Agfa Isolette

cameras included the 6×6 cm Isolette series, produced from 1938 until 1960. Agfa’s 6×9 cm cameras were the Billy Record series, introduced in 1927; these varied from very basic, entry-level cameras to some very respectable units with rangefinders and Compur shutters. Isolette and Billy cameras came equipped with one of three lenses: The basic Agnar , the Apotar (a triplet), and the Solinar (a four-element Tessar design). Even the midrange Apotar lens has been described as producing images of excellent quality. See Darryl Young and Jurgen Kreckel’s informative web sites for a more in depth discussion of Agfa cameras and some examples of the image quality obtainable with Agfa lenses at http://www.cleanimages.com/Article-MediumFormatInYourPocket.asp and http://www.certo6.com/index.html.

Agfa Billy Record III

E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., begun in 1842, was the oldest American manufacturer of cameras and photographic supplies. Scovill Manufacturing Company, likewise founded in the 1800s and the second largest photographic supply company in the U.S., purchased American Optical Company in 1871, and in 1889 was renamed Scovill and Adams. In 1902, these two photographic giants merged to form Anthony and Scovill. In 1907, the name was shortened to Ansco and the company was moved to Binghamton, New York. In 1928, Ansco merged with Agfa’s US subsidiary to form Agfa-Ansco.

Ansco and Agfa-Ansco produced large numbers of cameras, many of which were inexpensive, consumer-grade “snapshot” cameras, while some were of good quality. Many of the early cameras manufactured by the parent Ansco company used larger film sizes that are now unavailable, and should be considered strictly as display cameras. However, many more, such as the Ansco Isolette and Speedex cameras, were produced by Agfa, and the company also rebranded many cameras made by Chinon, Ricoh, and Minolta. The Ansco Speedexes are identical to the Agfa Isolettes.

Ansco Speedex Special R.

As candidates for fine art cameras using 120 roll film, Agfa-Ansco’s contenders out of its many products are the Isolettes (and their Ansco versions) in 6×6 cm and the higher-end Record cameras in 6×9 cm. Note that the cheaper models lacked slow shutter speeds, and should be avoided. Some later models had rangefinders and light meters; these are desirable options if in working condition.

BALDA:

Founded in 1908 by Max Baldeweg, Balda-Werk was one of the many successful camera companies in Dresden in the early 1900s. It made considerable numbers of folding cameras, some of which were sold to other companies. Balda cameras were fitted with a very wide range of lenses, from the low cost self-branded triplets through Meyers and

Prewar Baldax 6x4.5 cm

Ludwigs, to the high end Schneider Xenars and Xenons, and Zeiss Tessars and Biotars.

After WW II, Balda, like other Dresden companies, was nationalized under Russian control, and its founder fled to West Germany to start anew. Max Baldeweg set up a new company, also called Balda (Balda Kamera-Werk), this time based in Bünde, West Germany. This company produced a series of 35mm and medium-format rollfilm cameras, some of them being sold by Porst under the Hapo brand. The name of the East German company was changed to Belca-Werk in 1951 after considerable litigation; it continued to produce folding cameras, and was absorbed into the east German photo manufacturing conglomerate VEB Kamera-Werke Niedersiedlitz in 1956.

The original factory of Balda-Werk Dresden’s 120 roll film cameras included the Balda and Baldaxette in 6×4.5 and 6×6 cm, and the Baldafix, Juwella, Pontina (also sold as the Hapo 10 and

Balda Super Pontura

Hapo 45) and Super Pontura in 6×9 cm. The East German Belca plant manufactured the Belfoca in 6×9 cm format, and Balda Bunde produced the Baldi 29, Baldix, Mess-Baldix (Hapo 66e), Balda, and Super Baldax. All of the latter were 6×6 cm format.

The various Baldax cameras were well constructed and fitted with quality lenses and shutters. As such, they were extremely popular in pre- and post-war Europe. The only inexpensive cameras in the Balda line were the Juwellas, simple 6×9 cm self-erecting cameras with metal frame viewfinders and lenses of modest quality; they are not suitable for high definition work.

The prewar Baldax was made throughout the 1930s in three main variants: a 6×4.5 cm small model for #00 shutter size, a 6×4.5 cm large model for #0 shutter size and a 6×6 cm model (#0 size). All the Baldax cameras had solidly built diagonal struts, with a typical shape, larger at the base. Some had a folding optical finder and others had a tubular optical finder. The Super Baldax cameras were higher-grade versions of the parent cameras with coupled rangefinders.

The Baldix was similar to the 6×6 cm Baldax but lacked the frame counter. The Mess-Baldix was an improved variant of the 6×6 cm Baldix. Its optical viewfinder included an uncoupled rangefinder. It was available with an f/3.5 Enna Ennagon, f/2.9 Isco Westar or f/4.5 Balda Baltar.

The Pontina cameras, first produced in 1936-37, were rollfilm cameras with provision for both 6×4.5 and 6×9 cm exposures. They were available with a variety of quality lenses and optical viewfinders.

The Super Pontura is now rare, but was the top of Balda’s line of folding cameras designed for the demanding photographer. It featured a coupled rangefinder with parallax correction and a variety of lenses, including a 105mm Zeiss Tessar in a Compur-Rapid shutter.

ENSIGN:

With the exception of photo historians and camera collectors, Ensign cameras are almost unknown in the United States and Canada. I must admit, however, that I have a soft spot in my heart for these delightful little machines, and would heartily endorse several models for fine art work.

In 1834, George Houghton and Antoine Claudet partnered to found a glass company in London, under the name Claudet & Houghton, becoming George Houghton & Sons in 1892. The company’s headquarters were called Ensign House in 1901, and the company began producing roll film under the Ensign

The Ensign Logo

brand in 1903. In 1904, the company absorbed Holmes (the maker of the famed cameras), and three other companies (including A. C. Jackson, manufacturer of the Ilex cameras) to form Houghtons Ltd., continuing production of the Sanderson cameras until 1939. By 1908, the factory in Walthamstow was the largest camera factory in Britain.

In 1915, Houghtons Ltd. came into a partnership with W. Butcher & Sons Ltd, founding the joint venture Houghton-Butcher Manufacturing Co., Ltd. to share the manufacturing facilities. The two trading companies finally merged on January 1st, 1926 to form Houghton-Butcher (Great-Britain) Ltd., which was renamed Ensign Ltd. in 1930.

Ensign Catalog Page 1939

The headquarters of the trading company, Ensign Ltd., were destroyed by an air raid on the night of September 24, 1940. In 1945, the manufacturing company, Houghton-Butcher Manufacturing Co., joined with Elliott & Sons Ltd. (maker of the film brand “Barnet”) to become Barnet Ensign Ltd. In 1948 Ross and Barnet Ensign were merged to Barnet Ensign Ross Ltd., which was finally renamed Ross-Ensign Ltd. in 1954.

The company was remarkable for two reasons: First, for producing “… high-quality cameras … which can be considered to be superior in finish, and at least equal in performance, to the finest similar equipment produced in Germany up to that time… (S. Marriott, http://www.marriottworld.com/pieces/pieces29.htm). And secondly, for having the bone-headed stupidity to completely ignore the oncoming tidal wave of 35mm, and never even attempt to produce a viable 35mm camera! Consequently, like the passenger pigeon and the Siberian wolf, by the late 1950s this fine company had quietly faded away, with its assets auctioned off at bargain-basement prices.

As the waters have receded, however, some fine pieces of photographic equipment have been left behind on the shore. Of the many Houghton cameras, I would suggest that the reader give serious consideration to the Ensign Selfix series. These have been aptly described by Stephanie Marriott in the reference cited above; some of her comments are summarized below.

The Ensign Selfix 820 was described in a contemporary catalogue as “…Probably the finest roll-film camera, designed successfully to beat all the German competition both in optical and mechanical performance…” The camera body is die-cast metal covered in black morocco leather. The top of

Ensign Selfix 820

the body is finished in satin chrome, and the folding Albada viewfinder is located in the center of the top plate. A 105 mm.f/3.8 Ross Xpres lens is mounted in an Epsilon eight speed shutter. The cable-release socket is standard, but the flash sync socket is unique to the Ensign line, and the special Ensign connectors are virtually unobtainable. The Selfix 8/20 takes either 8 or 12 exposures on 120 roll film. Folding masks in the back of the camera allow either format to be selected and the viewfinder has markings for both. Given the propensity for drop-in masks to be lost during the forty-some years since roll film cameras were manufactured, this is a highly desirable feature.

The Ensign Selfix 820 Special is an 820 with a different top-plate assembly, which includes an uncoupled rangefinder and a nonfolding optical viewfinder. The viewfinder has a sliding mask for 6×6 cm. format. An accessory shoe is located on the top of the rangefinder. The Epsilon shutter fitted to the 820 Special usually has a standard 3 mm coaxial connection for flash.

The Ensign Selfix 16-20 (later called the Model II), yielding 16 pictures in 6×4.5 cm format on 120 film, was probably the closest Ensign ever got to producing a “miniature” camera in the post-war period. The design of the 16/20 follows the principles of the 8/20, but the top plate and the Albada viewfinder are combined in a streamlined shape. The Epsilon shutter is

Ensign Selfix 16-20

smaller and has a top speed of 1/300 sec. The lens is a Ross Xpres f/3.5 75 mm. One interesting feature is that the body release incorporates a blunt pin that presses into the user’s finger if one attempts to take a picture without advancing the film.

The Ensign Selfix 12-20 takes 12 6×6 cm images on 120 film. The design is similar to the 16-20, and the 12-20 uses the same lens and shutter as the 16/20. The shutter release and the camera front release are two chromium plated, tear-drop shaped buttons at the front of the top plate.

Some models of the Selfix cameras were equipped with the Ensar f/6.3 75mm lens. This is an extremely respectable lens and produces very sharp images. However, be aware that some of the cheaper models lacked slow shutter speeds and should be avoided.

FRANKA:

In 1909, Franz Vyskocil and his wife moved their small camera shop and factory from Stuttgart to Bayreuth in Bavaria. After several transitions, the factory received its final name, Franka-Kamerawerk. The company produced plate cameras until 1930, when roll film camera production began. In 1960, the company was purchased by Wirgin. Franka produced many models of 120 format folding roll film cameras, as well as still cameras in 16mm and 35mm format, until production ceased in 1966. Models to consider are the many Franka Solida models produced in 6×4.5 and 6×6 cm, some of which had rangefinders, and the 6×9 cm Rolfix models.

Rolfix camera production started in the early 1930s and continued into the

Rolfix II with f/4.5 Radionar

mid 1950s. The prewar models had flip-up optical viewfinders, while postwar models had enclosed viewfinders, and, in the case of the Rolfix IIE, an uncoupled rangefinder. Lenses were commonly an f/3.5 105 mm Rodenstock Trinar or f/4.5 105 mm Schneider Radionar in a Prontor or Compur-Rapid Shutter. Later models had provision for 4.5×6 and 6×6 cm formats with drop-in masks.

The Trinars and Radionars are both three element lenses (triplets) and have differing comments on their optical quality. Many photographers assume that a four element lens such as a Tessar is automatically sharper than a triplet and, as I have mentioned above, in actual practice this is not always true. Comments on photography discussion boards (photo.net is very useful in this area) suggest that prewar versions of these lenses can be soft at the edges at large apertures unless stopped down to f/11-f/22. Other comments suggest that “…triplets are fine lens, especially post war types which are coated and have the new Lanthanium glass…” and “…the Trinar is a very good lens. It is the only three element I continue to use in 105mm focal length 6x9mm format. I have a coated f2.9 version that seems every bit as sharp as my uncoated Xenar…” Both the Trinar and Radionar were fitted to these cameras in an f/2.9 version, and the availablility of these faster lenses may be a factor in favour of choosing a Franka camera.

The Solida family tree, oddly enough, had two branches: the Vertical Solidas, manufactured from the mid 1930s until the early 1960s, primarily for 6×6 cm with a few early 4.5×6 cm models, and the Horizontal Solidas,

Horizontal Franka Solida II with f/3.5 80mm Xenar

Isolette-style folders for 6×6 cm format with a few models having provision for the bizarre format of 4×4 cm. The Horizontal Solidas were produced from1953 through the early 1960s. After the war, the horizontal models became the Solida I, II, Junior and Record, while the vertical models became the Solida III series. In the horizontal series, the Solida IIs are preferable, as they are more sophisticated than the Solida I models, and the Junior and Record Solida cameras are basic models which should be avoided. A manual for the Franka Solida cameras can be downloaded at Mike Butkus’ web site at http://www.butkus.org/chinon/solida/solida_6x6_i_ii.htm

The vertical model Solida cameras came with Radionar or Trinar f/2.9 80mm

Verical Franka Solida IIIE with f/2.9 Radionar

lenses in one of the several models of Prontor or Compur shutters; occasional models can be found with Xenar lenses. Frankar, Westar, or Cassar lenses were less expensive, and probably lower quality, options. All had body shutter releases, and some models had engraved top depth of field scales. The III E models had an uncoupled rangefinder. Later Solida III L models were equipped with selenium light meters; the III EL cameras had both. The meter may or may not be an asset, depending on whether it is working and accurate. Overall, when in good condition, these are compact and very functional 6×6 cm cameras. Jurgen Krenkel comments of the Solida IIIE “…I’ve always found these to be excellent cameras and excellent optics…”

The horizontal model Solida II cameras came with similar Radionar/Trinar lens and shutter combinations. As with the vertical models, there were some additional lens types used, including the f/3.5 Isconar, Ennagon, and Westar lenses and f/4.5 and f/3.5 Frankar lenses. Franka purchased its lower-end lenses from a variety of manufacturers. Isco, founded in Gottingen in 1936, is still in existence today and specializes in cinema projection lenses. It has made lenses for a variety of camera manufacturers, and produced for Franka the Isconar and Westar lenses. Frankar lenses were made by Steiner-Optik GmbH of Bayreuth, a well-known manufacturer of binoculars; Steiner also manufactured camera lenses which were of reasonable quality. In accordance with the nomenclature of the vertical series, cameras designated E had rangefinders and those designated L had selenium light meters.

KODAK:

Kodak cameras will be discussed under their own heading.

VOIGTLANDER:

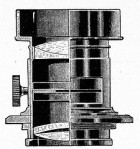

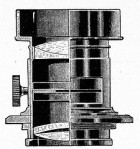

Founded by Johann Christoph Voigtländer in Vienna in 1756 , Voigtlander was the first factory for optical instruments and precision mechanics in

The Petzval Portrait Lens

Austria. In 1840, after the invention of the photographic process by Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre, Voigtlander produced the first camera lens designed according to mathematical principles. The Petzval portrait lens, created by Jozef Petzval, was, despite its distinct peripheral aberrations, one of the great lenses of the late 1800s, and has enjoyed a resurgence among present-day portrait photographers who strive for a “classic” look.

After a long history of producing quality cameras and lenses, Voigtlander became a part of Zeiss in 1965. In 1972 Zeiss/Voigtländer stopped producing cameras, and a year later Zeiss sold Voigtländer to Rollei. On the collapse of Rollei in 1982, the Voigtlander company was purchased by Plusfoto GmbH & Company, a buying cooperative of German photo dealers. Plusfoto sold Voigtlander in 1997 to Ringfoto GmbH & Company, a similar cooperative, who relaunched the company. In the late 1990s, Cosina licensed the rights to use the Voigtländer name and the names of Voigtländer lenses for its own products, introducing the Bessa series of 35mm rangefinder cameras. McKeown reports that the Cosina-produced Heliar lenses are of excellent quality.

Over the years when it was an independent manufacturer of cameras and lenses, Voigtlander has produced many fine cameras, as well as some that were cheaper and aimed strictly at the consumer market. In the category of quality folding cameras taking 120 film, the two series to consider are the Bessa 6×9 cm cameras and the 6×6 cm Perkeos.

There were many Bessas, starting in the 1920s and extending through the 1950s. One excellent model is the Bessa I, with the option of taking eight 6×9

Rear of Bessa I with Mask

cm exposures or 16 6×4.5 cm exposures with a removable mask that drops into the focal plane. Unfortunately, like most removable pieces on old cameras, it is usually missing. The viewfinder is integrated into the top housing and has parallax correction by a series of rotating masks. The lens is either a three element f/4.5 105mm Vaskar or a four element, Tessar-type f/3.5 105mm Color-Skopar. Although simple, the Vaskar is reported to produce excellent images. The shutters are Prontors or Compur-Rapids with speeds from 1 to 1/250 second. The Bessa I cameras retail at $35-100.

The Bessa II is of top quality and has excellent optics, being fitted with either

Bessa II with Heliar Lens

a Colour-Skopar, a five-element f/3.5 105mm Colour-Heliar, or, very rarely, a six element Apo-Lanthar. Focusing is unusual, being accomplished with a knurled wheel on the top left of the body that moves the entire front lens/shutter combination in and out. The viewfinder and rangefinder are combined in the top housing. The shutter is a Compur-Rapid or Synchro-Compur with a top speed or 1/400 or 1/500 second, respectively.

The main disadvantage of the Bessa II is that it is very expensive: prices for a Bessa II with a Colour-Skopar range from $300 to $500; with a Colour-Heliar, from $500 to $800; and with the Apo-Lanthar, from $2400 to $2800. My philosophy when faced with prices of this sort is that one should buy a lens that gives one the best possible images; this may or may not be an expensive lens. Past this point, spending large quantities of money is overkill. Superb work can be done readily with cameras costing under $100, and many of the images in this blog were done with Kodak cameras costing under $25.

The 6×6 cm Perkeo, a well made but fairly basic camera, came in three

Perkeo II with Colour Skopar

models: I, II and IIIe, all with a viewfinder enclosed in the top housing. The Perkeo I indicates whether the shutter has been cocked and has double exposure prevention, while the II adds a frame counter. The IIIe, which was produced only in small numbers, possesses an uncoupled rangefinder but lacks the frame counter. Lenses are either the Vaskar or a 80mm f/3.5 Colour-Skopar, mounted in Prontor or Compur shutters.

Frank Mechelhoff’s site has some excellent comments and complete diagrams of a large series of historical Voigtlander lenses.

WELTA:

Welta, founded in 1914 as Weeka-Kamera-Werk, was one of the many camera manufacturing companies in the Dresden area in the early twentieth century. Initially producing plate cameras, the company changed its name to Welta-Kamera-Werk and introduced roll film cameras circa 1920. 35mm cameras were introduced in 1935. The company became state run after World War II, and was finally absorbed into VEB Pentacon in 1964.

Welta produced two roll film cameras that should be considered: the Weltur,

Welta Weltur 6x9 cm

available in 6×9, 6×6, and 6×4.5 cm formats, and the Weltax, produced in 6×6 and 6×4.5 cm. The Weltur, produced from 1935 to 1940, had a rangefinder coupled to a focusing system that moved the whole front lens assembly. Earlier models had shutter-mounted releases, while later editions had releases mounted on the body. The Welturs came equipped with a variety of lenses, including a Cassar, Trinar, Radionar, Tessar, Trioplan or Xenar, mounted in Compur or Compur-Rapid shutter. A manual for the Weltur (in German) is available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/17619947/Manual-for-the-Weltax-camera.

The Weltax cameras were basically Welturs with body releases but without

Welta Weltax

the rangefinder. A top viewfinder had parallax correction. Like the Weltur, format was changed by means of drop-in masks which are often missing. Both the Weltur and the Weltax are extremely well made, and it is reported that images made even with the simpler Triotar lens can be enlarged to 24×36 in. The Weltax was produced both before and after World War II; there are some reports that claim that the postwar units were of lesser quality.

ZEISS:

A giant and major innovator among optical companies, the original Zeiss

Market Square, Jena

company, Carl Zeiss Jena, was founded in 1846 in the university city of Jena, in the province of Thuringia in eastern Germany. Originally a manufacturer of microscopes and scientific instruments, the company founded the Schlott Glass Works to develop specialized optical glasses for microscopes. Recognizing the potential of these new glasses for photographic lenses, the company hired Dr. Paul Rudolph, who designed the famous Anastigmat, Planar, and Tessar lenses. Zeiss entered the camera manufacturing business in 1902 with the acquisition of the Palmos A.G. Company.

In 1909, Palmos was transferred to the ICA group, and the Jena company returned to lens manufacture. In 1926, four camera manufacturers, ICA, Contessa-Nettel, Ernemann, and Goerz, merged to form Zeiss Ikon, which became one of the major photographic manufacturers in Dresden, with plants in Stuttgart and Berlin. After World War II and the partition of Germany, both Jena and Dresden became part of the Soviet-run eastern bloc. Zeiss Jena was assisted by the US army to relocate to the Contessa manufacturing facility in Stuttgart, where the new headquarters were set up. Camera and lens production continued through the merger with Voigtlander (see above) until camera production ceased in1972.

The East German component, VEB Zeiss Ikon Dresden, restarted production in 1945, but was forced to interrupt when the Russian Army took most of the existing Zeiss factory equipment, tooling and remaining personnel back to the Soviet Union to form the Kiev camera works as reparation for the destruction of Russian camera factories. Camera production resumed with manufacture of the famed Contax line. As a result of trademark disputes with Zeiss Ikon AG, the company was renamed VEB Kinowerke Dresden in 1958, and later formed a major part of the photographic conglomerate Pentacon.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany in 1990 had vastly different implications for the Eastern and Western divisions of Zeiss. The West German corporation was efficient and technologically advanced; its East German counterpart was nearly bankrupt, grossly inefficient, technically backward, and had a bloated staff of approximately 70,000. Sadly, only a portion of the staff and facilities were acquired by Carl Zeiss of West Germany. The history of post-reunification Zeiss is complex (for example, cameras named “Contax” had been produced on both sides of the Iron Curtain) and has been well documented on Company Seven’s web site at http://www.company7.com/zeiss/history.html.

Zeiss produced a number of important 120 roll film cameras suitable for fine art work; models that should be considered include the entry-level Nettar cameras, together with the Ikontas and rangefinder-equipped Super Ikontas.

The Nettars, designed as a low cost alternative to the more expensive Ikonta

Zeiss Nettar 517 6x6 cm

series, were one of the most commercially successful of all Zeiss Ikon cameras. Although simple and somewhat more lightly built than the Ikontas, they are worthy of consideration. Nettar cameras were available in 6×9, 6×6, and 6×4.5 cm formats, and were equipped with either Tessar, Nettar, or Novar lenses. The Tessar is preferred, although the Nettar and Novar lenses, both of which are three element lenses, have been reported to produce respectable results. There are some reports that suggest that both of these triplets are best when used stopped down. Prontor or Compur shutters are preferred; some models came with the cheaper Vario, Klio or Derval shutters. Viewfinders are of simple metal frame design except for those models with a viewfinder incorporated into the top plate assembly.

The Ikontas and Super Ikontas (equipped with coupled rangefinders) were

Zeiss Super Ikonta Model 531 6x9 cm

Zeiss Ikon’s top line of roll film cameras. Starting in the 1930s, a bewildering variety of Ikonta-series cameras were produced, with an equally bewildering system of nomenclature. A well organized and lucid account of the evolution of the Ikonta line and its model numbers can be found on Pacific Rim Camera’s Zeiss page (see below). The majority came equipped with Tessar lenses (or less frequently, a Schneider Xenar) in Prontor or Compur shutters, with a Novar lens in a Derval shutter, or a Triotar in a Klio shutter as a lower cost alternative. Prewar lenses were typically uncoated, while units produced after the war more commonly had coated lenses. Some later Super Ikontas were fitted with selenium-cell light meters. There have been some questions raised about the Zeiss Opton Tessar lenses, which should be of excellent quality. However, there have been claims on photography blogs that some of the postwar Optons were assembled by relatively unskilled staff and that the lens elements may not retain their position.

Many of the Ikontas came with simple metal frame viewfinders, while the

Zeiss Super Ikonta B Model 532 6X6 cm

Super Ikontas had Albada-type optical viewfinders. Later Super Ikontas models had the viewfinder and rangefinder base assembly incorporated into the top plate assembly. With the exception of the Super Ikonta III and IV, the last of the Ikonta line, the Super Ikontas’ typical appearance resulted from their rotating wedge rangefinder, which had the wedge located on an arm attached to the lens standard. All rangefinders were coupled except for the 6×6 cm “Mess-Ikonta” Model 524 6×6 cm, which had an uncoupled rangefinder incorporated into the top plate.

The Ikontas and Super Ikontas are of excellent quality, but it should be noted that they are rather expensive, falling in the range of $150-500. If the shutter needs to be cleaned, the overall cost will be approximately $100 higher. However, for this price, one gains excellent Zeiss optics, a large, high resolution negative, and precise rangefinder focusing.

A useful collection of technical notes and images of a number of classic roll film cameras can be found on A. MacPherson’s “Classic Cameras” web site. Some useful thoughts on lenses can be found on Beedham’s UK eBay Guide. Beedham has some interesting conclusions regarding the value of some simpler lenses versus more established names.

References:

Beedhams. “Choosing Medium Format Lenses – What’s in a Name?” eBay UK Guide. http://reviews.ebay.co.uk/Choosing-medium-format-lenses-what-apos-s-in-a-name_W0QQugidZ10000000000892177

Camerapedia and Wikipedia articles on Agfa, Ansco, Balda, Ensign, Voigtlander, Welta, and Zeiss.

Cohen, Martin C., “Carl Zeiss- A History of a Most Respected Name in Optics”, Online Posting, Company 7 web site, http://www.company7.com/zeiss/history.html.

“Ikonta”, Pacific Rim Camera, http://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/zeiss/ikonta/ikonta.htm.

Krenkel, J., “Vintage Folding Cameras”, http://www.certo6.com.

MacPherson, A. “Classic Cameras.” www.amdmacpherson.com/classiccameras.

Mechelhof, Frank. “VOIGTLANDER – Historial Lenses.” http://www.taunusreiter.de/Cameras/Bessa_RF_histo.html

“Super Ikonta”, Pacific Rim Camera, http://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/zeiss/sikonta/sikonta.htm.

Young, D., “Medium Format in Your Pocket”, Planet Nikon website, http://www.cleanimages.com/Article-MediumFormatInYourPocket.asp.

Profound thanks to Stephanie Marriott for use of the information on the Marriott web site, and to Darrell Young, Jurgen Krenkel, and the Living Image Camera Museum for the use of images.

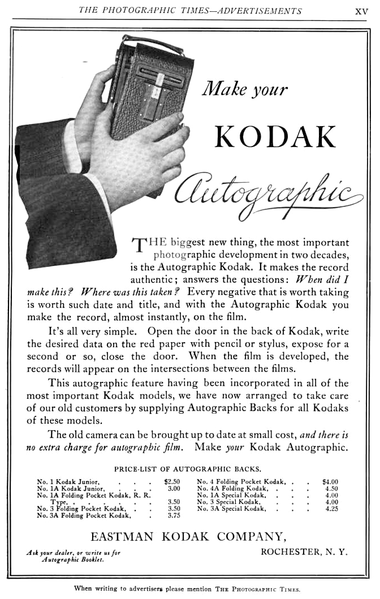

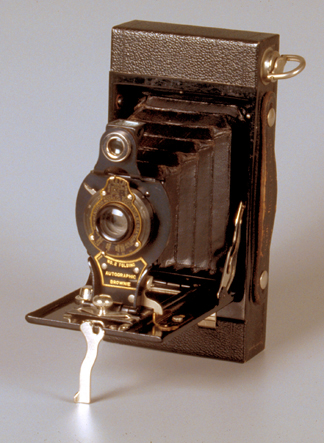

Subsequent evolution was rapid. By 1900, the drop front and focusing rail had replaced the struts of the original Folding Kodak (see Folding Kodak ad), and by 1902-3, models of the Folding Kodak were available with variable speed shutters and apertures, as well as

Subsequent evolution was rapid. By 1900, the drop front and focusing rail had replaced the struts of the original Folding Kodak (see Folding Kodak ad), and by 1902-3, models of the Folding Kodak were available with variable speed shutters and apertures, as well as