One of the most fascinating stories in photographic history stems from the search for a faster and better corrected successor to the Rapid Rectilinear lens. This quest culminated in the creation in the late 1800s and early 1900s of some of the most famous lenses of the twentieth century, many of which are in use today in only slightly modified form.

During the heyday of the Rapid rectilinear lens, only two kinds of optical glass, crown and flint, were available. Of the several kinds of aberrations that plagued lenses of this era, the most difficult to correct for was astigmatism. A result of the inability of the marginal portions of lenses made from ordinary crown or flint glass to bring to a focus in the same plane the images of lines radial to the lens and tangential to it, astigmatism was the most recalcitrant of the aberrations. The search for a true “Anastigmat” lens became the Holy Grail of lens designers for many years.

Mathematical analysis indicated that astigmatism could be eliminated by using glass of appropriate optical characteristics. In 1884 Dr. Ernst Abbe,

Dr. Ernst Abbe

then scientific director and partner of Carl Zeiss, joined hands with the German chemist Otto Schott and founded the famous glassworks at Jena. With financial aid from the Prussian government, their collaboration produced not only the dense barium crown glass of high refractive index required for the first anastigmat lenses, but also a long series of new types of glass of varied optical properties. As an added benefit, lenses made with the new glasses and corrected for astigmatism were also extremely well corrected for chromatic and spherical aberration as well as having extremely flat fields of focus.

The early anastigmat lenses built on the basic concept used in the Rapid Rectilinear lens, i.e., having two symmetrical or nearly symmetrical lenses on either side of an iris diaphragm, each composed of two or more elements cemented together. As in the case of the Rapid Rectilinear, many of the aberrations of the two lenses canceled each other out. In the case of the anastigmat lens, one of the pairs contained elements of barium crown glass of high refractive index; pairing this with a similar lens of conventional crown and flint glass elements allows correction of astigmatism as well.

The first true anastigmatic lens, the Protar, was developed in 1890 by Dr. Paul Rudolph, who was largely responsible for Zeiss’ domination of photographic lens design in this period. The front group was a standard

The Protar Lens

achromatic combination of low-refractive-index crown glass and high-refractive-index flint glass, but the rear group was an innovative achromatic doublet using Jena glass. The front and rear elements were located on either side of the diaphragm, effectively suppressing chromatic aberration.

Following closely on the heels of the Protar, the next famous lens was designed in 1892 by Emil von Hoegh. A more highly corrected optic employing in each pair a third cemented element intermediate in refractive index between the two external elements, it failed to catch the interest of Carl Zeiss. Fortunately for von Hoegh, the chief lens

The Dagor Lens

designer of the Goerz corporation had just died, and he won the position. Marketed as the Dagor (Doppel-Anastigmat GOeRz), it became one of the most successful anastigmats ever produced. Manufactured by the hundreds of thousands, it is still available on the used markets today.

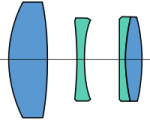

Another good quality vintage lens derived from the Dagor is the Goerz Dogmar, a further step in the evolution of the anastigmat lens. In a lens of the Dagor type, the efficiency of refraction depends on the difference in the refractive indices of the elements on either side of the cemented surfaces. The greater the difference in the refractive index, the shallower the curvature required and the more easily the lens is corrected. von Hoegh replaced one

The Celor/Dogmar Lens

of the cemented surfaces of each pair with an air space, raising the difference in the refractive indices across the glass-to-air interface and resulting in a simple lens of high efficiency. This lens was first introduced as the Celor in 1899, and after its design had been recalculated by W. Zschokke in a mildly asymmetrical form, as the Dogmar in 1916.

At Zeiss, introduction of an air space into the Protar design was to result in

The Tessar Lens

the development of one of the most successful lenses ever produced- the Tessar. In 1899, Rudolph replaced the cemented surfaces of the Protar with air spaces. The result was the Unar, issued in 1899, which had improved correction of aberrations and a larger aperture. In an effort to further improve corrections, Rudolph combined the two concepts- an air-spaced element and a cemented element- in the Tessar, which was first issued in 1902. The front component of the Tessar consisted of two lenses separated by

A Cutaway View of a Tessar Lens

an air space having a dispersive effect and resembling the corresponding element of the Unar. The rear component consisted of two cemented elements having a collective effect, the entire component closely resembling the rear element of the Protar. The name “Tessar” was derived from the Greek word tessera (four), indicating a four-element design. It has been claimed that the Tessar is a descendent of the Cooke Triplet (see below), but it is clear that this famous lens is a logical development of the Protar with replacement of one cemented surface by an air space.

The Tessar design was licensed by Zeiss to other lens makers of the period. After the patents expired, it was copied by almost every major optical manufacturer (a partial listing is available in the Camerapedia entry at www.camerapedia.org/wiki/Tessar). The Kodak Anastigmats, the most popular lenses on good roll film cameras of the 1920s, are Tessars, as are their legendary offspring, the Kodak Ektars. A number of other excellent lenses represent modifications of the Tessar design, most notably the excellent Ross Xpres, the premier lens of the English Ensign roll film cameras; this is a Tessar design with the rear component consisting of three cemented elements instead of a doublet. The Xpres was introduced in 1913 based on a design by by J. Stuart and J. W. Hasselkus. The rear triplet served two functions: it to some extent reduced zonal spherical aberration, and it allowed the designers to bypass Zeiss’ patents!

While Carl Zeiss and C.P Goerz were developing lenses based on the concept of the symmetrical doublet in Germany, a new family of lenses was being born at the famous English telescope manufacturer Cooke. In 1893, H. Dennis Taylor, scientific director of Cooke, invented a lens consisting of three single elements separated by air spaces. The Cooke triplet, as it was to become known, consists of a central negative biconcave flint glass element with a positive crown glass element on either side. In this design, the

The Cooke Triplet

negative lens can be as strong as the outer two combined, so that the sum of the powers (diopters) of the elements can be zero, yet the lens will converge light. Since the curvature of the field is related to the sum of the diopters, the field can be very flat. At the time, the Cooke triplet represented a major advance in photographic lens design, being very highly corrected and having the additional advantage of being very light and compact. After the patents expired, this design was copied by multiple optical manufacturers. Many of the later Cooke lenses are still considered desirable acquisitions for large format work. Cooke is still a well known manufacturer of lenses for cinematography (see http://www.cookeoptics.com/cooke.nsf/pages/index.html).

One of the greatest accomplishments of the Cooke triplet, however, was that it was the progenitor of one of the most famous lenses ever produced. In 1902, Harting calculated for the German firm Voigtlander a five-element system consisting of two cemented doublets with a singe biconcave negative lens between them. It is thus a true triplet, with the external lenses consisting of two cemented doublets instead of the single elements of the  Cooke lens. These changes helped address the Triplet’s shortcomings of longitudinal aberration while still allowing for a fast aperture. The lens had a speed of f/4.5 and covered 50 degrees. Its large aperture made it suitable for portraiture and work at fast shutter speeds. Issued by Voigtlander as the Heliar, it is still one of the most highly regarded lenses ever manufactured, and the classic Heliars, produced for a variety of film formats, command respectable prices to this day. The Heliar went through numerous modifications, including one incarnation marketed as the Dynar, up into the 1960s; these have been carefully documented in the Antique and Classic Cameras web site (http://www.antiquecameras.net/heliarlenses.html). For the kind of 6x9cm (2 1/4 x 3 1/4 in) medium format work discussed here, the Heliar lenses are most commonly found on the Voigtlander Bessa roll film cameras and the famous Bergheil plate cameras.

Cooke lens. These changes helped address the Triplet’s shortcomings of longitudinal aberration while still allowing for a fast aperture. The lens had a speed of f/4.5 and covered 50 degrees. Its large aperture made it suitable for portraiture and work at fast shutter speeds. Issued by Voigtlander as the Heliar, it is still one of the most highly regarded lenses ever manufactured, and the classic Heliars, produced for a variety of film formats, command respectable prices to this day. The Heliar went through numerous modifications, including one incarnation marketed as the Dynar, up into the 1960s; these have been carefully documented in the Antique and Classic Cameras web site (http://www.antiquecameras.net/heliarlenses.html). For the kind of 6x9cm (2 1/4 x 3 1/4 in) medium format work discussed here, the Heliar lenses are most commonly found on the Voigtlander Bessa roll film cameras and the famous Bergheil plate cameras.