Like most of us, I shot film until digital came along because of all of the new and modern add ons that came along with it, like a lens extender so I could get those really good angles, and then my backpack of expensive German glass languished in the cupboard for years. That lasted until five years ago, when I bought a 1920 Kodak for $10 on eBay and ran my first roll of film through it. Although light leaks and bad exposures plagued most of the frames, one image of an antique gas station was excellent, with pleasing color and subtle tonal gradation. I was hooked. I realized for the first time that equipment from the early part of the century could produce striking, professional-quality images. Better yet, I achieved beautiful results with both black and white and color film. As a result, most of my work is now done with my collection of cameras made between 1900 and 1930. They don’t just sit in their display cabinets, either. My cameras, the result of many hours of patient restoration, are old and beautiful, but they’re like sled dogs- they work for a living.

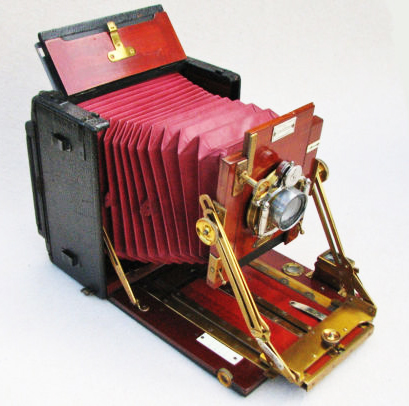

I prowl eBay for old Kodaks from the 1900s and 1920s. They have black leather bellows that pull out, and lenses named “Rapid Rectilinear”, “Anastigmat”, and “Tessar”. Many of these old lenses yield photos with a lovely “feel” unlike those from modern, mathematically perfect lenses. Bodies are covered with rich leather, and metal parts gleam with chrome or burnished brass. No flash- indoor pictures were taken by setting up the camera, turning out the lights, holding up a piece of “flash paper”, and lighting it with a match while your subjects held their smiles in the dark!

The No. 1 Kodak Junior

My present camera is a 1914 No.1 Kodak Junior, the “No. 1” indicating that it takes 120 film. In an era when enlargers were unknown and roll film came in sizes up to five inches wide, this was the miniature camera of its day. It has two shutter speeds, 1/25 and 1/50, together with T and B. F-stops are marked in the old U.S. system with 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 equaling modern f-stops of 8, 11, 16, 22, and 45. The lens is an uncoated Rapid Rectilinear. Designed in the late 1800s, it nevertheless rewards me with razor-sharp images. If I want to be “modern”, I pull out my lovely, near-new 1928 No.1 Kodak with its four shutter speeds and crisp f/6.3 105mm Anastigmat lens for a days’ outing in search of old barns and farmhouses.

Image processing is by a hybrid approach combining the best features of film and digital. My film is typically Ilford XP-2 for black and white or Kodak VC-160 for color. Both have fine grain and generous exposure latitude. Using film lets me record a tonal range of approximately seven stops, compared to the six-stop range usual with a digital chip. The negatives are then scanned, allowing me the full creativity and flexibility of processing in Photoshop.

There are challenges, however. I puzzled over streaks ruining my night photos until I remembered shining my flashlight into the film counter window to read the numbers on the film. I quickly bought a red flashlight for winding the film in the dark. Old bellows often leak light through pinholes at the corners. I finally found a liquid plastic used to coat screwdriver handles that sealed the tiny holes but remained flexible and didn’t crack.

These old relics are not simple to use; the older the camera, the more ways there seems to be to mess up a picture. Why I persist in this particular form of insanity is anybody’s guess, but it is habit-forming. One might think of this affectation as the photographic equivalent of bow hunting, where one maximizes one’s frustration and discomfort, and gives the prey every possible chance to slip away. However, I suspect that my affection (frequently unrequited) for the look and feel of brass lenses and old camera leather is probably incurable.

The results are worth it. I cherish the lovely tonal qualities of a marsh in the afternoon light, or the patterns of Palouse wheat fields after harvest. I love night photography, stalking old churchyards to capture the eerie mood of my shadow projected among eroded tombstones, or pondering the image of a floodlit Spanish mission. I always marvel at the rich color from a lens created forty years before color film appeared on the shelves.

The cameras are old, but they keep me young. I’m an inveterate explorer, and am always looking for an old barn, an abandoned car, or a group of gnarled trees to capture as images in my beloved antiques. With luck, I will be wandering the back roads with my beloved relics for many years to come.

I began this site, first as a blog and now as a web site, to share with others the wonderful rewards that I have gained from working with these old masterworks of brass, glass and leather – not just the pleasure of owning or collecting them, but of actually using them and seeing the wonderful images that they can produce. I hope to share with you what I have learned about evaluating and purchasing vintage cameras, cleaning and restoration, and shooting techniques with uncoated lenses, limited shutter speeds, and primitive viewfinders. In between, I may add some thoughts on the creative process and a few stories about my adventures as an itinerant vintage-camera photographer. I hope that you find even a fraction of the rich pleasure that I’ve gained from these wonderful old machines.

The majority of images on this site are done with cameras between sixty years and a century old; along the way, a scattering of digital images have crept in. Some of these illustrate specific photographic situations for which only a digital image is available, while others demonstrate the differences in effect or capability between digital and full frame silver-emulsion photography.

T. Rand Collins MD

Duncan, B.C. Canada

Note- This posting appeared in modified form in the Fall 2009 issue of Canadian Camera magazine.