A wide variety of fungal species can infect camera lenses; these include the families Phycomycetes, Ascomycetes and fungi imperfecti (see Gordon Stalker, “Fungus and Cameras”). The potential for fungi to permanently damage lenses depends on the species. Some species secrete acids and other substances that will etch coatings or the glass itself. While some of these secretions are waste by-products, others are related to the fungus’ mechanisms for collecting nutrients. It has also been suggested that some presumed etching may actually represent insoluble deposits left behind by the hyphae (see “ESWAT: Fungus and Camera Lenses”).

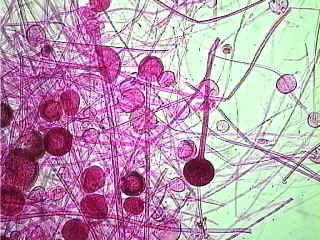

Fungi are the primary decomposers of organic material and can break down most organic compounds. However, they derive little nutrition from the glass or its coatings, relying instead on organic contaminants found on surface of the lens, such as oil films, dust, or remnants of the materials used in the construction of the lens assembly. Fungi grow as delicate filaments, called hyphae, and reproduce via spores which are produced by fruiting bodies. The

latter can be quite large in the case of the familiar mushrooms and toadstools (the actual fungal mass is buried in the underlying soil, and may cover acres), but are usually microscopic in size. Fungal spores are extremely small, and find their way into virtually all spaces.

The significance of fungus growth on a camera lens depends on whether it infests the surface of the glass or the cement between the elements. In older lenses, elements were cemented together with Canadian Balsam, turpentine made from the resin of the balsam fir tree (Abies balsamea). Due to its high optical quality and the similarity of its refractive index to that of crown glass, Canadian Balsam was used in the first half of the twentieth century to cement glass elements, but was phased out after World War II in favor of polyester, epoxy and urethane-based adhesives. Being an organic material, Canadian Balsam provides varied and nutritious fare for fungal species. Growth in the cement is usually fatal to the lens, as treatment requires the complex and expensive process of uncementing, cleaning and reglueing the affected elements; growth on the surface can frequently be cleaned if the acids secreted by the fungus have not etched the glass.

The degree to which lens fungus is a problem depends greatly on where you live. In my cool Pacific Northwest climate, it does not seem to be a significant problem. In parts of the United States where there is considerable summer humidity, it is definitely a consideration. With the Ansco, the occurrence of fungus only on the rear element that was exposed to the closed environment within the bellows, which would retain humidity and would dry only slowly, makes perfect sense. In tropical climates, fungus is enough of a problem that camera shops offer routine lens cleaning services. In these climates, photographers expose their lenses to sunlight or ultraviolet light, or buy drying cabinets for storing their equipment. Toomas Tamm’s site provides a fascinating glimpse into tropical photographers’ battle to keep fungus at bay.

Cleaning fungus from lenses may require only careful but determined cleaning with a good aqueous lens cleaner and a soft cloth or Q-tip. Other authors have cautioned against using Windex, but I have found it an effective cleaner on older, uncoated lenses. Kodak Lens Cleaner or dilute vinegar are good alternatives. Kleenex, despite its reputation for treating swollen noses kindly, actually has a content of harsh fibers (not to mention piles of lint) and should be avoided in favor of Kimwipes, which are recommended by professional cleaners of scientific optical equipment. I soft lens cleaning cloth is the ideal option. Be sure that you carefully remove all dust (something of a challenge with very dirty older lenses) before wiping with tissues and cleaners.

For more serious cases, naphtha and ethanol have been recommended, as have silver polish, toothpaste, and cold cream. I have had no experience with these remedies. To disinfect the lens and kill the fungus, hydrogen peroxide, bleach, and thymol have likewise been recommended (see Gordon Stalker’s site). My prejudice is that effective disinfection of the lens housing can only be accomplished by complete disassembly and disinfection of each individual part; failing this drastic move, one may be best served by cleaning the glass surfaces and then keeping the lens dry, thus depriving the fungus of needed moisture.

One of the most fascinating and useful discussions of lens cleaning in general, with some specific comments on removing fungus, is the thread on “Camera Cleaning” on Rick Sammon’s blog. This thread has been running for 12 years (since 1998)! It is an enormously useful compendium of opinions on the best way to clean camera lenses and is well worth reading in its entirety.

References:

ESWAT Blog. “Fungus and Camera Lenses.” Online posting, May 4, 2009. http://faculty.clintoncc.suny.edu/faculty/michael.gregory/files/bio%20102/bio%20102%20lectures/fungi/fungi.htm.

Gregory, Michael. “Clinton Community College Biology Web: Fungi.” http://faculty.clintoncc.suny.edu/faculty/michael.gregory/files/bio%20102/bio%20102%20lectures/fungi/fungi.htm.

Sammon, Rick. “Camera Cleaning.” Online thread. http://photo.net/learn/cleaning-cameras.

Stalker, Gordon Ian. “My Pentax: Fungus and Cameras.” http://www.mypentax.com/Fungus.html.

Tamm, Toomas. “Fungi in Photographic Lens.” http://www.chem.helsinki.fi/~toomas/photo/fungus/.

Wikipedia Article. “Canadian Balsam.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_balsam.

Pingback: Fungi on rear lens element.... - Leica User Forum

Pingback: restoring + cleaning your vintage camera | Pearltrees