The Question

Let’s face it – every artist is a predator. Writers use their childhoods, their mothers, their life experiences (Tennessee Williams and the sordid South, Hemingway and the Spanish Civil War). Painters use atrocities (Picasso and Guernica) and their mistresses. We all take from our surroundings and companions to feed our art. Often, the result is beautiful and restorative. Sometimes the relationship is symbiotic; consider Alfred Steiglitz’ erotic images of Georgia O’Keefe that built her career. And often it’s downright parasitic – let’s not even talk about the National Enquirer and the paparazzi.

When I’m out on the street with my camera, I often see people in terms of images – and I’m hunting. No jungle cat with an empty belly could be more alert for its prey. The temptation is always to shoot someone – anyone – who would make a dramatic image. This is the essential moral dilemma of the photographer: how far are we willing to go to make a statement?

Much has been written about this dilemma. I think that this question was best summed up by Ruth Fremson, a photographer for the New York Times, who has see much suffering through her lens:

“I don’t set out to exploit another person’s suffering in order to make art,” she said. “I set out to tell a story, to explain a situation, to enhance viewers’ understanding of the world around us.

“The way a photojournalist can drive home the severity of a situation, for readers to fully understand them, is to make the most compelling image possible from an event — an image that will make someone stop for a moment, take it in and give the situation some thought.

“A photojournalist who has mastered the visual tools of composition, the use of light and color and the ability to capture the ‘decisive moment,’ will be able to produce a photo so compelling that it can be described as beautiful — or perhaps even as art — even if the subject matter is one of pain and suffering.

“Interestingly, museums around the world are filled with art that depicts human suffering, often based on real events in history…”

This does not keep artists’ work from generating controversy, however. Consider Shelby Lee Adams’ images of the the inhabitants of the “hollers” of rural Appalachia. His images are powerful and exquisitely printed, yet critics charge that “…his photography exploits the poverty and disempowerment in Appalachia and reproduces negative stereotypes…” (Wade,2009).

Berthie on Bed, Shelby Lee Adams, 1996

My impression is that those who do not want such images shown are ashamed of these people, and consider them ignorant hillbillies. Yet are they not saying more about themselves and their own ignorance than about their less financially-blessed neighbors? I have lived and worked in Appalachia, and know something of the dignity of the Appalachian people, their deep sense of family, their adherence to Christian values, and the incredible richness of their culture. Those dwellers in the hollers who live in poverty and lack education have created a wealth of music, song, and crafts that is unique in the American experience. Those same black-lunged miners who peer out from Shelby Lee Adams’ portraits can be virtuosos at the bluegrass and miners’ laments that express their ability to survive and triumph over oppression.

Dewey Henson and Banjo, Shelby Lee Adams, 2010

Creativity and richness of experience more often spring from hardship, adversity, and suffering than from a comfortable life and a steady paycheck. Consider the black experience in the United States – what people could have been more repressed and downtrodden, yet they gave us the blues, jazz, rap, and rock and roll? Who, viewing the images of slave quarters and, later, slums and housing projects, would have predicted that America would become known by the music created from this legacy of poverty and degradation?

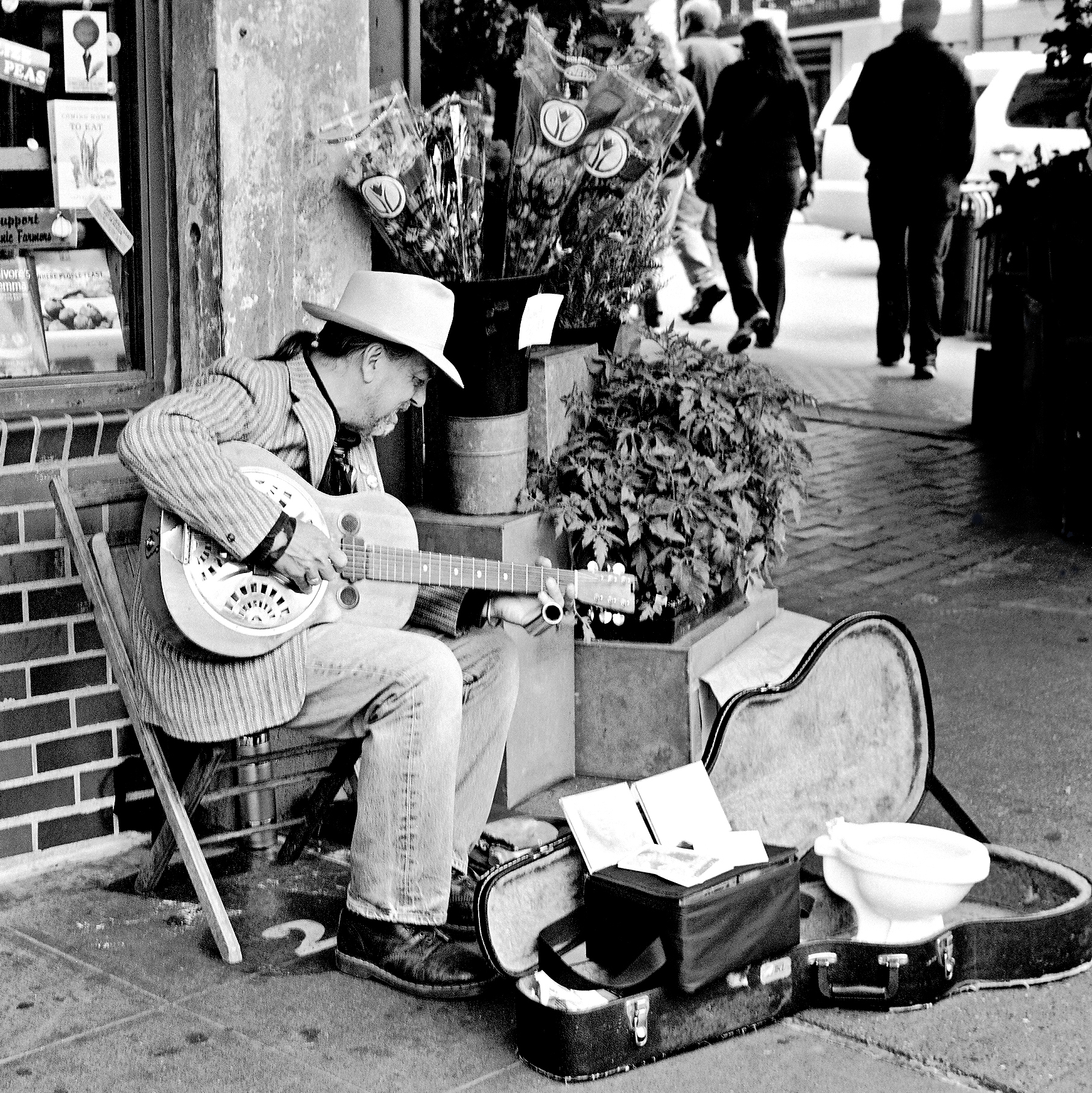

I struggle with these questions every day that I am on the street with my camera, and constantly try to balance my art with my sense of my subjects’ dignity. Yet even in this process, often the most rewarding part of the experience is the connection with the people in my pictures. I met this gentleman sitting in a doorway on Seattle’s Broadway, itself a rich palette of street cafes, college students, and many who spend their days on the streets. Many of the individuals one meets on benches and doorways are obviously in pain, and if I photograph them, it is from a distance and in a manner that preserves their anonymity. But many, if one stops to visit, are delightful and original. This gentleman gave me a quick smile as I stopped to talk, happily agreed to have his picture taken, and even offered me a choice of messages on his sign! I was late for a meeting, and unfortunately, could not stop to visit with him.

This image was taken with the Ensign 16-20 on Kodak VC-160, and appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Camera magazine.

References:

Adams, Shelby Lee, Blogspot blog. http://shelby-lee-adams.blogspot.com/.

Documentary Films, “The True Meaning of Pictures.” http://www.docurama.com/docurama/true-meaning-of-pictures-the/.

Estrin, James. LENS- Photography, Video and Visual Journalism: Forum – Suffering and Art. http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/06/16/forum/.

Johannes, A-M. News Media’s Depiction of Human Suffering. http://amjohannes.wikidot.com/news-media-s-depiction-of-human-suffering.

Reinhardt, M. et al. “Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain.” University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Wade, L. Online posting, “Sociological Images” blog, “Art and Representation”, Jan. 17, 2009. http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2009/01/17/art-and-representation/.