Wapasu Bus Lot, A Sloppy Day in Late Winter

Wapasu Bus Lot, A Sloppy Day in Late Winter

Sometimes I find myself in a place where I’m sure there ‘is nothing to photograph. I am almost always wrong.

No matter how sterile or seemingly dull the environment, you can always find a story to tell and something to shoot!

The Bagup Room – a delicious piece of Newfoundland terminology, translated to the middle of the subarctic boreal forest and an oil boom that powers Canada’s economy. Past overall-clad figures in studded safety boots, I toss sandwiches, fruit and salad into a paper bag, then sidle past the exquisitely bored Somali guard in the dining room. Grabbing a tray from the pile, I shovel orange and grapefruit slices into my bowl, and line up for a neatly institutional square of omelet, followed by a dipper of oatmeal in a white china bowl.

Dawn at Wapasu Lodge

Exactly eleven minutes to eat breakfast, then through the Wapasu Lodge doors into a blast of cold in the predawn Arctic darkness. I shuffle out with a hundred more thickly bundled

Waiting for Brass Alley

figures to wait under the baleful red lights of Brass Alley. Lights flash red to green, and we

Brass Alley

shuffle forward through turnstiles. Out the Alley’s back door, we hurry in the glare of halogen lamps studding tall pylons into rows of buses whose diesels growl into the blackness.

Such is morning at Wapasu Camp in Canada’s northern Alberta oil sands. Researcher, doctor, photographer, driver of big trucks – I am now a Health, Safety and Environmental Trainer/Industrial Hygiene Specialist, working for Chicago Bridge and Iron, helping build Imperial Oil’s Kearl Lake Oil Sands facility in Alberta’s subarctic North Country.

My “work week” starts around 10 am when Janie drops me off at Maple Bay, a secluded cove about ten minutes from our Vancouver Island home. I stand with my bag and computer pack at the end of the wharf amid houseboats and pleasure craft. Soon a small float plane buzzes into view and skims in for a landing. My bags are tossed on board, and

My “Other Car” – the de Havilland Beaver at Maple Bay

I climb in beside the pilot, trying to keep my knees from banging the stick and my feet off

Riding Shotgun on the Beaver

the pedals. We roar up the bay, climbing into the air over boats, forested islands, and summer homes, glide into Salt Spring Island’s picturesque little harbour to pickup a couple more oilfield workers, and 30 minutes later glide over Richmond’s crowded suburbs to touch down on the Fraser River. I walk three block to the commercial South terminal at the airport, and two hours later join a crowd of about 200 rugged-looking men and women heading north on Canadian North’s chartered

Boarding Canadian North at Albian Sands

jet. Two hours later, we are landing at Albian Sands airport, a strip of tarmac without even a control tower in the middle of the snowy Northern Alberta wilderness. We crowd into a row of snowy (or muddy, depending on the season) Diversified Transport buses for an hour’s ride to our respective camps, where we line up for our room assignments, haul our stored bags our of the luggage room, and settle down for a night’s sleep before an early morning and another bus ride to camp.

I rise at 4:45 every morning for 20 days, then pack my belongings off to storage for eight days at home. This is known as “Working a 20 and 8 cycle.” I later move to a “14 and 7” cycle – two weeks on and one week off – which is much more civilized. My days are spent in my classroom trailer, teaching orientation courses and introductory safety topics to electricians from Ireland, pipe insulators from California, and boilermakers from West Virginia.

Stereotypes paint construction workers as burly men with tattoos, beer bellies, and not much between the ears. The reality could not be more different. Many will surprise you with their depth of knowledge and thoughtful intelligence. Louis L’Amour, the famous writer of western and adventure stories, talked about the many self-educated men he met in the west (see Education of a Wandering Man, Random House, 2008).

The workers at Kearl are likewise a diverse and fascinating group. One shared that he is a fossil collector from the Maritimes. A self-taught, graduate-level amateur paleontologist specializing in the invertebrate fossils of New Brunswick, he corresponds professionally

The Guys I Teach

with museum directors across Canada and has original theories on the dating of the first land creatures. His talk of ancient eras and documentation of Eastern Canada land mass movements left me in the dust.

Kearl Lake from the Air (Anonymous Photographer, early 2012)

One big Irishman plans working hard and saving for five years, then retiring to care for his partner, who has multiple sclerosis. Another is an avid photographer who just got back from a job in Spain where he had time to photograph the Alps. A third, a quiet man from San Salvador, spent three years in the jungle as a guerrilla after union membership brought death threats. Scottish cement contractors mix with safety experts from coal mines in Nova Scotia, and rub elbows with insulators from Cape Breton. A wonderful cross-section of the world, their stories stretch from Canada’s blustery Maritimes to the forests of the West, opening little windows on Somalia, Ireland, South America, and China.

The classroom banter is the best part, and the camaraderie with my fellow teachers – language gets rough but I love working with these guys:

Morning chatter in the trailer (tasting my coffee carefully, making sure they didn’t sneak in an extra bag and supercharge it):

Me: Good morning, guys. Is anybody awake???

Big Mike, my fellow teacher, wanders through the class with his first cup of coffee.

Me: “Guys, this is Mike Knoll. He’s a very good teacher, but he is always insulting people.”

Mike: “Come on! I’ve been here a whole half hour, and I haven’t told anyone to fuck off yet!”

Ty (sticking up his hand): Can you tell me when we’re supposed to go home?

Me: I can’t tell you when to go home. Only your company can do that. What’s the matter? It hasn’t even started to get boring yet.”

Ian (Older guy with one arm, sitting next to Ty): Don’t be so anxious to leave. You’ll give the guy a complex.”

We all go around the room, introducing ourselves.

Big guy with black hair: I’m a trucker. I drive truck on the site. I’m 52, I live in Ontario, and I got ten kids and one foster kid.

Me: You’re going to be up here a long time. Those little beggars are expensive. By the time I discovered that, it was too late. You must have a big house!”

Big Guy: Seven rooms. It’s not too bad, except when the girls all get on the rag at the same time. Then it gets interesting! (Grins) When they get on each other, I just tell them to shut the fuck up so I can watch television.”

Paul (tallest, skinniest guy I’ve ever seen, wound up like the Energizer Bunny): “My name’s Paul. Everybody calls me Paul F. That’s for “Paul F…. Welder.’ I got my five rules to live by. They’re tattooed on my arm (and they are).

Me: “Meet me later. I want to photograph your arm.” And I do.

Paul’s T-shirt is pink. The front of it says “All my black shirts are dirty.”

I introduce myself part way through the introductions, show pictures I’ve taken, talk about my cameras, our time in the mountains of Kentucky, and the walks and images I take here in the marshes.

Paul (privately, afterward): “Hey, I know all the trails around here. I’m a bootlegger.”

One guy is a guitar collector. One spends his money to travel the world. Ian is an underwater photographer.

Next lecture – My other fellow teacher, Libertad, is from Peru but lives in Colombia, where she has to worry about workers who keep machetes in their tool bags when labor relations get touchy. She spent many years in mines high in the Andes. She’s great on getting the guys moving and doing role playing. Have you ever seen a dozen big, whiskery construction workers up on their feet like a bunch of kindergarten kids, acting out the two-arm hand signals for moving a crane the size of a house???

And so it goes….

Life is never dull up here…

Wing 39, Wapasu East

The people are fascinating, but the place? Wapasu in the winter can only be described as bleak and institutional. Rows upon rows of barracks-like prefabricated buildings fill the skyline of the Arctic night. There’s no doubting their usefulness and the speed in which they can be constructed and taken down again, but visually they leave a lot to be desired. Corridors, gray and blue and lined with aluminum siding, stretch into the distance, pockmarked with endless rows of doors, differing only in their numbers. Workers are camera-shy, and photographing people seems like an intrusion. In contrast, the Kearl construction site is fascinating, with enormous yellow cranes rearing starkly upward in the morning sun, and flames burning balefully in the darkness to heat huge vessels about to be welded – but photography is forbidden. I am reduced to scattered pictures taken unobtrusively at camp with my Droid X smartphone or an old Canon point-and-shoot.

Evening At Wapasu Camp

Yet as I walk evening after evening around Wapasu, its wings rearing like huge fingers out of the snow, illuminated by the halogen glare, I see that night and the light lend it a stark, monolithic beauty. Inside, the corridors, if institutional, are striking in their symmetry. I begin to experiment with my Droid and camera. As I become one with the human river flowing through the turnstiles and into the buses in the Arctic darkness, my Droid sneaks almost by itself out of my pocket. I begin to snatch profiles of huddled figures silhouetted against Brass Alley’s red glow, and try frame after frame to catch movement as workers hurry for buses.

After a Long Day – Back to Camp

As Wapasu becomes my home for three weeks per month, I bring my favourite framed photographs. Pastel rugs decorate the floors, and vintage cameras crown my armoire, together with loving cards from my wife. I come to realize that the camp is warm and cozy on the inside, with a Tim Horton’s and a little general store. Meals in the dining room include prime rib, Cornish game hen, an immense spectrum of desserts, and many varieties of salad. Pool and table tennis are available. Decor is austere and prefab, hauled-in-by-a-truck-and-bolted-together institutional, but housekeeping is excellent, the staff are friendly, and we can decorate our rooms to our taste.

Much to learn, and I have joined a culture unknown to most of the world. Meet the rodbuster”” – he cuts and bends rebar for concrete foundations. The “rigger” connects the cable for cranes that lift tons of steel. Zoomer stops by my trailer – he drives a “Zoom-Boom”, a contraption like a forklift on a huge extendable arm, mounted on four enormous

Teaching fall Protection – My friend and fellow instructor Libertad

tires, and capable of lifting loads forty feet in the air onto scaffolds and elevated work sites. I learn about – and then teach – scaffold safety and the physics of falling wrenches. Life is not dull. A pile driver piston fractures on Thursday; the top fragment blows out of the cylinder and 300 feet into the air, landing at the base of the driver: 16 inches diameter, 30 inches long, and 2500 pounds of solid steel that misses everyone because of well-designed safety barriers.

I learn more about my new construction culture. Brass Alley? A long trailer, studded with red lights and and multiple doors with turnstiles, no brass within miles, and it is called Brass Alley? Intrigued, I investigate, and find threads linking me to builders and miners of the last century. “Brass”, dollar-sized brass discs, were issued to miners and builders as a method of timekeeping on mines and large projects before the computer age. Each miner would “brass in” – collect his token – as he passed through the gate of brass shack at the beginning of the shift. A missing token at the end of the day meant a miner unaccounted for (see The Brass System).

The origins of my new safety profession are written in the blood of miners and workers. Hillcrest, Alberta, 1914 – 189 dead, 400 children fatherless. Westray, Nova Scotia, 1992 – a small Cape Breton community changed forever from “incompetence, mismanagement, bureaucratic bungling, deceit, ruthlessness, coverups, apathy, expediency and cynical indifference.” It is no wonder that my bible, the summary of Alberta’s safety legislation, is called “The Red Book.” Each dry law and code traces back to a miner buried, a hand lost, or a life changed.

Evenings are for dinner, work on my web site, and walks. In winter, the latter are adventures. Wolves are about, the largest about 150 pounds, requiring a canister of bear mace that bounces on my hip. Breath congealing at -17 Fahrenheit, my snowshoes sink into the powdery snow as I break trail up a seismic cut. I must be adventurous; 7,000 people in this camp and I am the only one out in the woods tonight. I have one mysterious friend who has gone before me, their narrow cross-country skis leaving tracks into the Arctic darkness. The tracks turn right into the forest, and I follow, my light catching snowy jewels off the stunted arctic spruce as the trail snakes through a miniature frozen lake, mounds of snow gleaming in the brilliant beam. In my hidden lake, I take refuge from the industrial glare in pools of frosty darkness between the spruce and tamarack. Despite the industrial-grade camp lights and institutional setting, walking the forest roads near Wapasu can be a surreal and beautiful experience. Over the snow-crowned tips of the spruce, the horizon is studded with pools of pearly white light, gleaming off the low-hanging clouds. Visible from space, these opalescent pools of light mark other camps and claims surrounding Wapasu – Firebag to the west, CNRL (Canadian Natural Resources Limited) to the north.

Despite the industrial-grade camp lights and institutional setting, walking the forest roads near Wapasu can be a surreal and beautiful experience. Over the snow-crowned tips of the spruce, the horizon is studded with pools of pearly white light, gleaming off the low-hanging clouds. Visible from space, these opalescent pools of light mark other camps and claims surrounding Wapasu – Firebag to the west, CNRL (Canadian Natural Resources Limited) to the north.

Oil sands from Space

Despite being huge mines and industrial complexes, their glows dot the horizon like pearls on a necklace.

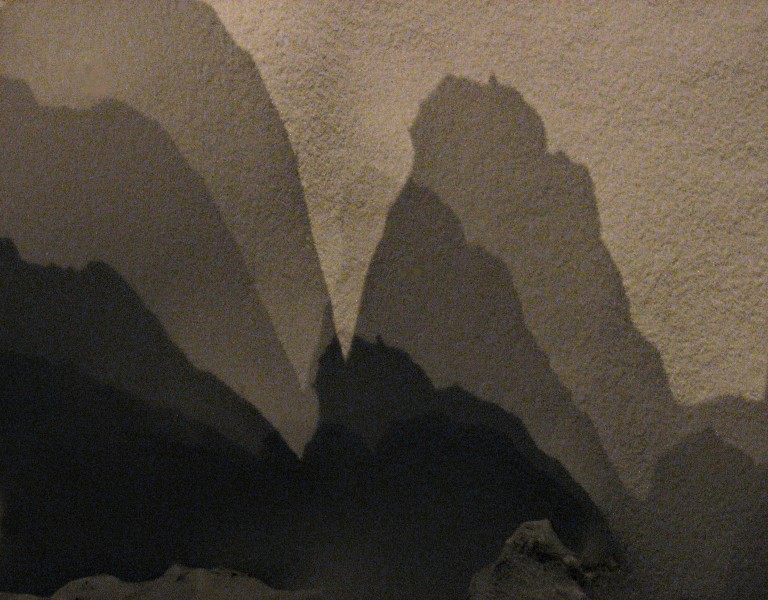

As my surroundings soak into my consciousness, surreal and beautiful images begin to coalesce out of the harsh industrial lighting. Like the upturned brushes of some giant boreal artist, a grove of leafless white poplars gleams in the light cascading from the

Poplars, Jupiter, and Aldebaran, Wapasu Camp

camp. A tripod improvised from a cardboard box and a pile of snow captures their glowing crowns, with Jupiter and Aldebaran suspended above. Next rotation, I return with a huge old Mamiya tripod. A monstrosity at home, in Wapasu, it is perfect, with long legs that  Wapasu Camp from Forest Snowshoe Trail

Wapasu Camp from Forest Snowshoe Trail

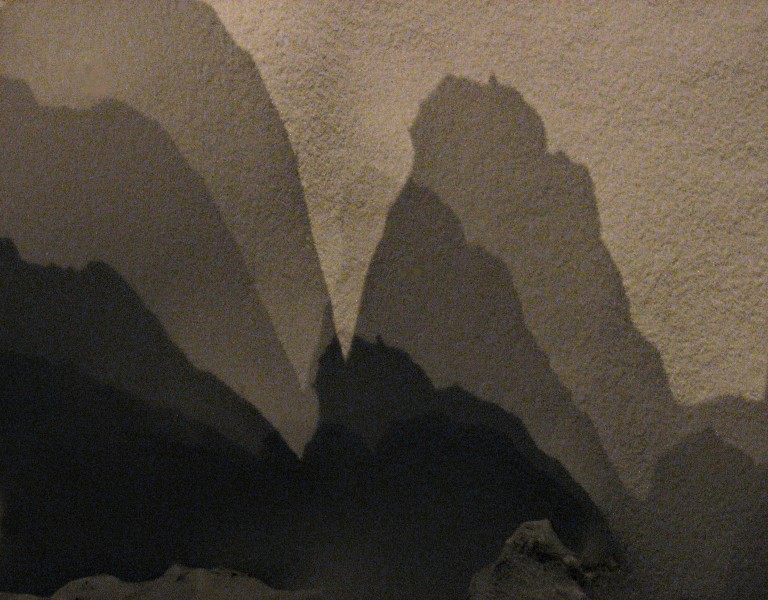

disappear three feet into snow and still leave me plenty of tripod for my little camera. Lugging its bulk one-handed with my poles in my other hand, I set out nightly. Prowling the margins of ugly snow piles, an abstract of shadows paints the fresh snowy surface, their

Snow Shadows 01

darkness piled layer on layer. As I walk, I have not one shadow but four, with long stilted legs and a head lost in forest. Farther on, roadside snow mounds are an abstract in

Long-Legged shadows

crystalline lines and deep shadow. The play of halogen light and shadow creates many abstract shapes, creating images of stark simplicity. A single twig in a snow bank stands out, silhouetted against a band of black shadow. At each stop, my little Canon is dwarfed on its huge mount, but its shutter clicks faithfully – until the batteries and my naked fingers succumb to the cold.

Twig and Shadow

An anomaly among camp dwellers, my sanity is questioned: “Man, you’re crazy…There’s animals out there!” Likewise, there is much negativity about camp life. Google Earth’s citation on Wapasu is filled with comments like “This place sucks” and remarks on the terrible food.

My Room at Wapasu

Like much of life, Wapasu is what you make of it. Consider the coyote. One of the most successful animals on the planet, the coyote thrives from the blistering Mexican desert to the frozen tundra of Alaska. He can be found in and around most large North American cities, where he will cheerfully make off with your garbage or Fluffy the cat to feed his mate and pups. His secret? He is amazingly, wonderfully, adaptable. In my own way, I am a coyote in this austere place, making a den for myself and finding a way to grow, flourish, and pursue my art within the Gulag. On the bare walls of my little room, I improvise clips over moldings to hang my artwork, scrounge colourful old mats from my basement, and cut bulrushes from a ditch to make a corner flower arrangement. Vintage cameras adorn the dresser, together with cards from my wife. Audio books play on my computer, and my austere room suddenly feels like home.

Be aware, however, that this adventure requires preparation, and does not work for everyone as well as it has for me (see Geoff Dembicki’s “Oil Sands Workers Don’t Cry“). Being up at four or five am daily and working a 10 or 11 hour day is tough, especially if you are hanging tank insulation at -30 degrees. Heart attacks are not uncommon, though numbers are hard to come by. One worker dropped dead at the table in the east wing while I was enjoying my trout in the west dining room. Isolation is hard, and you need to plan for ways to feed your spirit. The process is especially tough with young families, and fathers or mothers who cannot be home. Just getting sleep can be a struggle, and fatigue feeds depression. One worker’s significant other called him in the middle of a class to demand a divorce. A nurse told me that many strong, superficially tough men have closed her office door and burst into tears. One needs to go into this experience with an eye on one’s health: take favourite hobbies, music and books, get exercise, choose healthy options in the food line, socialize, talk with your family about managing separation and child care. It can be a great experience – or a miserable, lonely time.

But if you can adapt, it can be a good life. One red-haired young ex-schoolteacher said, “This is fun!” Apprentice pipefitters praise the experience: “Man, I’d never get to do this stuff in Toronto!” Another schoolteacher, driving a house-sized heavy haul truck, said “I made my year’s salary in three months.” Humour helps: “Kearl Correctional” hoodies are common. A crane operator’s T-shirt blares, “Heavy Lifting Starts at a Million Pounds.” One hefty fellow’s back says “Fat people are harder to abduct.”

So each night, I strap on my snowshoes to visit the jewel-encrusted tamaracks and firs. And once again, almost without my willing it, images climb through the lens of my camera and onto my film. No matter where I go, or how unpromising the place, they find me, and I must take them home and look after them.

There is always something to shoot.

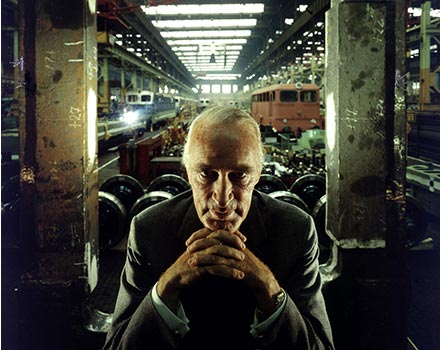

Rand at Kearl

Postscript: My kids saw my Wapasu images and asked, “What did Dad do to get sent there???

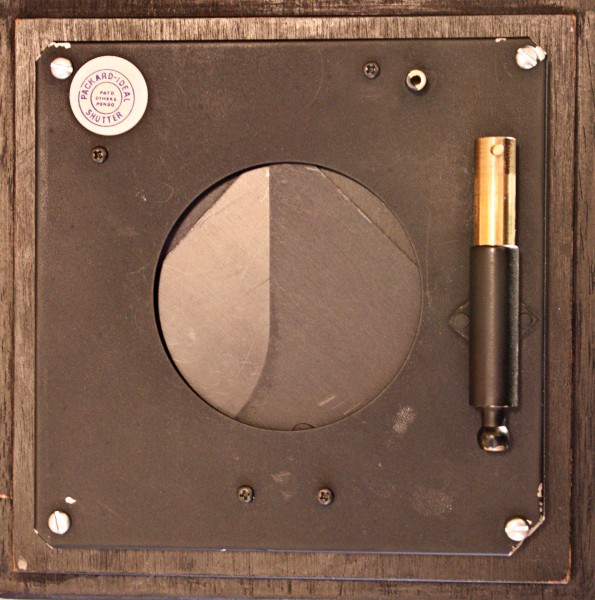

Note: These images are all digital, taken with a Motorola Droid, a Samsung Galaxy 4, or a small Canon A610 point-and-shoot on Aperture Priority.

Wapasu Bus Lot, A Sloppy Day in Late Winter

Wapasu Bus Lot, A Sloppy Day in Late Winter

Despite the industrial-grade camp lights and institutional setting, walking the forest roads near Wapasu can be a surreal and beautiful experience. Over the snow-crowned tips of the spruce, the horizon is studded with pools of pearly white light, gleaming off the low-hanging clouds. Visible from space, these opalescent pools of light mark other camps and claims surrounding Wapasu – Firebag to the west, CNRL (Canadian Natural Resources Limited) to the north.

Despite the industrial-grade camp lights and institutional setting, walking the forest roads near Wapasu can be a surreal and beautiful experience. Over the snow-crowned tips of the spruce, the horizon is studded with pools of pearly white light, gleaming off the low-hanging clouds. Visible from space, these opalescent pools of light mark other camps and claims surrounding Wapasu – Firebag to the west, CNRL (Canadian Natural Resources Limited) to the north.

Wapasu Camp from Forest Snowshoe Trail

Wapasu Camp from Forest Snowshoe Trail