Note: All of the images of Hazard are digital (Canon A610 point-and-shoot), as I did not have a vintage camera during that trip, and many pictures were lost when my hard drive crashed in 2007. The photographs here are those that survived, and are supplemented with images from various web sites. This article was written after I returned to Canada in 2007

***************************************

Remember The Dukes of Hazzard? There really is a Hazard, Kentucky (one z only, thank you), and I and my wife Janie spent the best year of my professional life there.

This seldom-visited corner of America struggles with poverty and unemployment, but has given rise to one of the richest cultural heritages in the United States. However, I am not going to talk about the beauty of the Appalachian Mountains in the morning mist, or the spring wildflowers, or the bluegrass festivals, or the Appalachian handicrafts- they are all there, and they are rich and wonderful. Instead, I am going to focus on the Appalachian people that I met and with whom I worked, their stories, and what they taught me about myself and how to live. And along the way, I’ll share some images that may help to bring this little-known world to life.

Appalachian Regional Health Medical Center, Hazard, Kentucky

In February 2006, I accepted a six week assignment at the Appalachian Regional Health Service hospital in Hazard, Kentucky, a major rural medical teaching center affiliated with the University of Kentucky. The six weeks stretched into a year full of experiences and stories. Janie, whom I left in our new house with a garage full of boxes and no blinds on the widows, finally gave up and joined me. She made nutritious meals in the tiny kitchen of our hotel suite, made friends, and became a counselor at the rape crisis center.

Hazard, Kentucky (Courtesy www.city-data.com)

LIFE IN APPALACHIA

Southeastern Kentucky lives on coal. When the world buys coal, mine shifts run twenty-four hours a day, and families eat well. When coal sells poorly, work is scant, mines close down, and Appalachian families go hungry. Poverty and hardship are part of life in the mountains. Often Appalachian towns aren’t pretty; old buildings are abandoned and crumbling, paint peels from ramshackle houses, and Wal-Mart is the premier place to shop. Yet never have I met people who have a stronger sense of their roots, their family, and their faith.

Driving the narrow back roads around Hazard, I was puzzled to see how people lived in the “Hollers” – the islands of arable land between the mountains. Used to seeing affluent and working-class neighbourhoods in American and Canadian cities, I noted modern, large and well-kept homes next to log cabins or rundown mobile homes. In each of these tiny communities, a rusty sign directed me to a cemetery on a hillside above each collection of homes. Each cemetery was well-kept, and included only a few family names. Slowly I realized that these were family communities where one or a few families lived together, rich next to poor – a testament to the strength of family in these tiny mountain communities. I learned later that many Appalachian people will endure the regional poverty and lack of jobs rather than give up their family connections.

Many Appalachian towns are tiny- a collection of ten or twenty houses, a gas station and maybe a store, tucked into the bend of the river or a corner of a holler between the mountains. They have names like “Viper” or “Scuddy” or “Fourseam”. Many houses are old, often representing old coal company housing, and people are obviously poor. Yet in the middle of each of these little towns is a church with fresh paint, a parking lot without a blade of grass in the asphalt, and a neatly painted sign. In a year in the mountains, I saw only one church that wasn’t impeccably kept. Most mountain people have deep religious faith, and “family values” has real meaning.

Appalachian Coal Camp Town, Harlan County, Kentucky (Still image from the film “Harlan County USA”)

Appalachian Baptist Church, Cades Cove

In Hazard, I met the warmest, most generous people I have ever known. If you do not greet complete strangers as you pass on the street, you are considered rude. Family is unbelievably important. The waitress at the local coffee shop supported herself, her mother, and a retarded sister by working two jobs. I don’t know if there are old people’s homes in Southeastern Kentucky; I never saw one. Elders are valued members of the family, and Appalachian people make great sacrifices to care for them to the end of their lives.

The man who installed computer cables throughout the hospital summarized it for me when he told me,”I left the mountains and worked construction in Florida when I was younger. I was making good money, but I didn’t know anyone. One day I asked myself what I was doing there, threw my tools into the car, and drove back to Hazard. I lived my first winter in a log cabin with a leaky roof, and I cooked on an old stove I found, with coal I picked up on the roadside. I didn’t have any money, but my aunt took me in and kept me fed. Now I got me a little piece of land. It’s mostly mountainside, but it’s mine. If you ain’t got a piece of land, you’re nobody. If I get in trouble, I know someone in my family will take me in and feed me. I got a nice little house, water from the spring, and my family’s here. What more do you need?”

I thought about how many times I’d wished for a newer car or worried about my bank account. I doubt that I will ever think about those things in the same way again. I learned more from the people of Appalachia than I could ever teach.

AFTER DARK WITH A CAMERA

My experiences were rich. During the day,I am a night person, and an avid photographer, so I do a lot of night photography. I can be found lurking in churchyards at midnight, taking photographs of tombstones standing starkly in the light from a single street lamp.

Shortly after arriving in Hazard, I and my camera were out one night exploring Combs, a little town that climbs up the side of a mountain to an old cemetery at the top. I paused to take a time exposure of one street that went up the mountainside between huge maples, their bare branches stark in the illumination of the streetlights. I noticed people peering out of the windows of the house next to me. I could see someone making a phone call, then neighbors arrived, and soon there was a group at the widow watching me. Finishing my exposure and not wanting to alarm anyone, I went to the gate and began to explain my peculiar behavior to an elderly woman who was just leaving the house. She snapped “I don’t hold with that kind of stuff” and stomped off. I was perplexed. This wasn’t the friendly Kentucky I was used to.

I walked up to the top of the hill, finding an old shack beneath an enormous maple tree, illuminated by the light of a single lamp- a wonderful picture. By this time, I had acquired a pack of neighborhood dogs, who surrounding me, barking vigorously. As I was setting up my picture, a man and a woman came out of a nearby house. The woman held back, while the man approached, asking me what I was doing. I explained, showing him some of my pictures. He grunted and walked off. Once more I was puzzled, not being used to this kind of reception.

The next morning, I mentioned to the lab manager that I had been in Combs, and asked if it was safe to wander around there after dark. She replied, “Oh, you’ll be fine. People are good to strangers. They just shoot their relatives.” Then she added, “But you know, there used to be an old shack up on the top of the mountain by the cemetery, and a drug dealer used to sell his stuff out of there”. Apparently, this was where I had been taking my photographs. In my Doc Martens and Eddie Bauer vest, I clearly wasn’t a local. Obviously, I was either another dealer looking to set up shop, or a government agent. Neither was popular in that town.

I later learned that shooting your relatives is still not an uncommon way of settling family disagreements in Appalachia. Fortunately, I was not related to anyone in Combs.

On my time off, I would spend evenings and weekends hiking the many mining roads that crisscrossed the mountaintops near Hazard. At the end of the day, I would sit on the mountainside on the steps of an abandoned coal processing plant, watch the sun go down, then hike down the mountain listening to the cacophony of frogs, watching the fireflies and searching for glowworms among the fallen leaves. It was there that I heard my first whippoorwill. I collected fossils, which are plentiful in coal country, and learned about Kentucky’s native plants. One day, I brought home a beautiful little ivy, which lived for some time in a pot in my hotel room. Unfortunately, when I took it to my office, I was informed that it was poison ivy and was made to take it home. I felt rejected. By this time, I was attached to it. I smuggled it home to Canada in a box of books and still have it.

I love stories, and was delighted to find that storytelling was a rich tradition in Hazard. At break time, the laboratory staff would sit over coffee, telling me stories about their families and colorful characters they had known.

To understand many Appalachian stories, it is necessary to realize that this area was largely cut off from the rest of the United States until the turn of the century, when the coal companies built railroads to service the mines. Families lived in isolation, usually one family to a “holler”, with mule trails connecting communities, until well into the 1930s. Families were close, and members of a community looked after each other. Unfortunately, family feuds were also common, and were often settled with bullets and buckshot.

However, if there was a problem, the sheriff might not arrive for a day, and only after someone hiked over the mountains to fetch him. Telephones were unknown. For this reason, people in the mountains had to know how to protect themselves. To this day, most households have four or five guns of various type and calibers, and many children learn to shoot and hunt as soon as they are old enough to lift a rifle. I learned from the staff that the caricature of the Appalachian granny with her double-barreled shotgun has a strong basis in fact. Many of the older ladies in the mountains have not forgotten how to use a shotgun, and are not shy about using it on the unwary stranger who wanders into their property after dark, usually before they ask for an introduction.

My favorite story was told to me by Arthur, the cytotechnologist, who was commenting on how much he missed his “Granny Lil”.

One Saturday night when he was eleven, Arthur was staying with his grandparents, and had just gone to bed. He noted that the little road up their holler passed within a foot of Lil’s front stairs. Around 11:00, a carload full of local boys, all drunk to the gills, wavered up the road. As they passed Lil’s front stairs, they all yelled out, “Y’all sleepin’ up there?” Lil, who was somewhat excitable, grabbed up her Smith and Wesson .38 caliber revolver as she headed for the door, saying to her husband, “They’re gonna to be robbin’ us next!” On the porch, she turned on the light so that she could see to shoot better, and proceeded to empty her revolver at the taillights of the car as it disappeared around the bend.

A few minutes later, after the car had had to turn around at the end of the road, it reappeared and pulled to a stop about 75 yards away. All of the passengers piled out of the car, and it was soon apparent that they were both drunk and armed. The whole group quickly began to blaze away at Lil, who, continuing to take her stand under the light, was a perfect target.

Arthur’s grandfather was terrified, and yelled, “Get down, Lil. You’re gonna get shot”. She totally ignored him, and, standing under the porch light, proceeded to empty her revolver at the car, calmly reloaded, and emptied her revolver again.

Fortunately, all of the combatants were fairly safe, as the occupants of the car were too drunk to shoot straight, and Lil couldn’t hit the side of a barn in broad daylight. After a while, everyone ran out of ammunition, the car drove away, and Lil went back to bed.

I said, “But what did the neighbors think of this?” Arthur replied that every once in a while, their dogs would start making a ruckus in the middle of the night, setting off all of the dogs in the holler. This was more often a coon or a possum than an intruder. Lil would jump out of bed, seize her trusty .38, and, going out on the porch, would yell, “Who all’s out there?” Receiving no reply, she would begin firing in the general direction of the noise. The dogs would crawl under the house, and nothing more would be heard from them for the rest of the night. Arthur noted that all of their outbuildings were liberally peppered with holes.

Hearing the commotion, the neighbors would sit up in bed, wondering if they should go outside and check on things. Hearing Lil starting to shoot, they would crawl back under the blankets and go back to sleep, knowing that they we safe while she stood guard. They dubbed her “Pistol Packing Lil”, and there was remarkably little petty crime for some distance around her farm.

It is thought-provoking to note that this all happened in the mid 1980s, only twenty years ago. Some things in the mountains have not changed much.

MINING LIFE

Map of the Harlan Coalfield

Unfortunately, other aspects of life in the mountains also have not changed. Mining coal is still a hard and dangerous life. After many years of coal’s unpopularity as a fuel, prosperity is returning to the mountains, mines are reopening, and mining companies once again place ads in the papers.

This is, however, a mixed blessing. Mines that have been closed for years are now reopening- with thirty year old equipment, and mine owners who skimp on updates, maintenance and safety training. Accidents that make national news are infrequent. Yet talk with the wives and the children, and you hear the personal tragedies- the back that is wrenched and causes lifelong pain, the wages lost for everyday injuries, the husband crushed in a roof collapse, or the miners killed in an explosion from defective gas baffles installed by poorly trained men. You see them one or two at a time in the halls of the hospital- the men who are missing a leg, an arm or fingers, or limping down the corridor, or hobbling by on crutches. Fingers and toes with lacerations, crush injuries, and evidence of complete or partial amputation trickled across the cutting table as I processed afternoon specimens. Safety citations are issued, but in reality, companies pay fines, citations accumulate, and compliance is difficult to enforce.

This is, however, a mixed blessing. Mines that have been closed for years are now reopening- with thirty year old equipment, and mine owners who skimp on updates, maintenance and safety training. Accidents that make national news are infrequent. Yet talk with the wives and the children, and you hear the personal tragedies- the back that is wrenched and causes lifelong pain, the wages lost for everyday injuries, the husband crushed in a roof collapse, or the miners killed in an explosion from defective gas baffles installed by poorly trained men. You see them one or two at a time in the halls of the hospital- the men who are missing a leg, an arm or fingers, or limping down the corridor, or hobbling by on crutches. Fingers and toes with lacerations, crush injuries, and evidence of complete or partial amputation trickled across the cutting table as I processed afternoon specimens. Safety citations are issued, but in reality, companies pay fines, citations accumulate, and compliance is difficult to enforce.

These abuses are not new. Much of the history of the mineworkers’ struggles in the 1920s and 1930s took place in Southeastern Kentucky and West Virginia. Union organizers were derided as “Commies”, “Bolsheviks” and “Red Necks”, the latter term referring to the red bandanas that striking workers often wore. With the collusion of local police, mineworkers were blacklisted, arrested, beaten and murdered. The “Bloody Harlan” strike of 1931-32 was just that- bloody ( see “Bloody Harlan).” In 1932, Jim Garland, a miner and union organizer, was forced to flee Harlan County and escape north for three months. On his return, he composed the song “”Welcome the Traveler Home”, telling his fellow miners “…I was expectin’ to be put in jail… so I composed this song”. One verse goes:

“…When I get back to Kentucky,

And I get my .45’s on,

There’ll be another Boston Tea Party

If they try to welcome this Red Neck home…”

Another old miners’ song from the 1920s, “Red Necks”, epitomizes the violence between scabs and miners:

“Red Necks, keep them scabs away,

Red Necks, fight them every day.

Now any old time you see a scab passin’ by,

Now don’t hesitate- blacken both of his eyes.

Red Necks, don’t admit defeat,

Don’t give up this fight.

We’re goin’ to win this strike

Things again are goin’ to be all right.

You’ve got to keep the scabs away!”

There was many an organizer who made it out of Hazard alive by burying himself under the load of black gold on an outgoing coal train.

The mine owners were not the only group the miners had to worry about. Although exact estimates are hard to come by, the mob also had their fingers in the lucrative pie of Southeastern Kentucky.

John, my pharmacist and a long-term collector of local folklore, was a gold mine of stories of the old days in the Hazard area. My favorite was his tale of Al Capone’s visit to Hazard:

“In the 1930s, the mob was very active in the mines. There used to be an old rooming house across from the fire station. One night, Al Capone, visiting to direct bootlegging and the mob’s other operations at the mines, spent the night in an upstairs bedroom. Somehow, this news reached the Hazard police, who decided to apprehend him. After gathering in force in the fire house, they rushed to front door with guns drawn. Bursting though the door, they were met with a shower of high-powered bullets from a military-issue machine gun mounted on the stairs. A fierce firefight ensued. Finally, both Capone’s men manning the gun were dispatched, and the police rushed up the stairs. To their consternation, they discovered that a rear stairway exited from the upstairs to the river, and Capone had escaped out the back as the police were shooting it out with his minions downstairs.”

On a lighter note, crime was not always a bad thing for Hazard. A few years ago, a local arsonist did the city fathers a considerable service. Driving down Main Street reveals a partial block of brick buildings gutted by fire, their shells punctuated by empty windows like eye sockets in a rusty skull. One of these buildings was the old Hazard Hotel. This establishment, besides being he only good accommodation in the 1960s, was also home to most of Hazard’s ladies of the night. The loss of the hotel, their main place of business, significantly diminished the sex trade in town. However, some of the ladies, undaunted by this calamity, purchased a small Winnebago and parked it down by the river near Al Capone’s old domicile. The locals soon dubbed it “The Shag Wagon”. It was a fixture of town for many years until business became too profitable, when it was finally closed down by local police.

With respect to the practice of medicine, I was continually challenged by cases usually seen only in tertiary care medical centers. Despite hard-won reforms and better working conditions, coal mining still shortens miner’s lives. I was told by one miner that the average coal seam in Kentucky is approximately two feet thick. To extract the coal, many miners spend their shifts lying on the mine’s floor parallel to the seam, grasping a narrow cutting machine that gouges out the coal (see NIOSH information on seam height and injuries). Each miner at the front of the cut is teamed with a partner. Breathing apparatus is issued, but many miners do not want to have communication with their partner hampered in any way, as the price of a second’s delay in a collapse can be serious injury or death. Consequently, the apparatus is not worn consistently, and miners still die of black lung. We did the autopsies, and widow’s compensation not infrequently hung on the results of our work.

Not all the dangers are in the mines. Health consciousness is simply not a part of the culture, the result of decades of isolation and limited access to adequate health care. The population of southeastern Kentucky is second in the nation in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diet is an insurance agent’s nightmare. Salads come topped with ground cheese, and fries are commonly eaten smothered in gravy. At Franny’s Diner in Hazard, the appetizer list includes deep-fried cheese balls. .Keeping up on one’s vegetables, however, is not difficult – the “Vegetables” part of the menu includes macaroni and cheese. It also lists deep fried squash, as well as some items that I didn’t know could be deep fried. . Bypass surgery occurs in the forties rather than in the sixties. The majority of people smoke, having started as teenagers, and this exacerbates the effects of diet and coal dust inhalation. Most noticeable is the incidence of morbid obesity; football-shaped women and, to a lesser extent men, are common. Changing these attitudes is difficult, and I gained a profound appreciation for the power of cultural inertia.

I asked my own doctor, a talented and dedicated young family practitioner from a nearby county, where I could find a good personal trainer. He just smiled tolerantly and informed me that, in his opinion, a personal trainer would starve in Hazard.

However, the mountain people accept hardship, illness and injuries as part of living. Most importantly, death is viewed as a part of life. One day, one of the housekeepers at the hotel, who had been briefly absent, mentioned that she had attended an uncle’s funeral. I expressed my condolences, and then asked if his death had been sudden, or expected as a result of illness. She answered, “Oh, I think he expected it. He went and dug his grave two days before”. I reflected on how death today can feel like a defeat for the physician, as well as the fact that a goodly part of the cost of medicine occurs as doctors or relatives push to prolong the last few months of life. I hope that I can deal with the inevitability of my own death with this degree of acceptance and composure.

As a result of unemployment and poverty, drugs, primarily marijuana and Oxycontin, are a significant problem. However, the dynamics of drug dealing are complex and different in the mountains. The State of Kentucky receives considerable revenue from coal taxes. However, these funds, like a river disappearing in the desert, seem to leach into the ground in the more affluent and vote-rich areas of the state, with only a trickle reaching the people who earn them. This engenders considerable bad feeling, and there is a definite lack of loyalty toward the state government. Many drug dealers fix roads and bridges, becoming an asset to the community, and receive protection in return. After a raid on his house revealed ten tons of marijuana in a basement vault, the largest dealer in the county escaped in his truck up a creek bed and eluded police for months. He was thought to have hidden in caves in the mountains and to have been supplied with food by his neighbors. He appeared regularly to give interviews with local reporters, while embarrassed police hunted him fruitlessly.

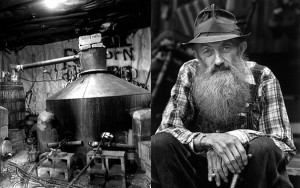

I was curious to meet local moonshiners, who are a dying breed. However, I abandoned any thought of sampling their product when I learned that it is typically condensed in old automobile radiators. The only scientific paper that I found on this topic reported a depressing list of trace elements, heavy metals, and toxic hydrocarbons.

My own work as a pathologist was varied, challenging, and provided an education that I have not had since residency. Fibrous knots surrounding deposits of coal dust were common in lung biopsies. A textbook case of bronchoalveolar carcinoma crossed my desk. The ovoid fatty tumor I received one afternoon weighed in on the pediatric department’s scale at five pounds, and sections revealed a liposarcoma. Greenish lumps of tissue originated from a gangrenous scrotum; I have yet to understand how one can let one’s scrotum become gangrenous. Opening a lump of skeletal muscle from the calf revealed a mangled bullet, the result of a family disagreement. Careful measurements with my micrometer on several axes were averaged to .25 caliber, and this was duly noted in the pathology report.

Most surprising were the gastrointestinal biopsies. At least one in twenty showed fibrotic deposits of coal dust in the wall of the small or large bowel, a testament to the amount of dust swallowed by the miners. To date, I have yet to find another pathologist who has even heard of intestinal coal dust granulomas, nor have I found any reference in the literature. I came to appreciate the price of our plastics and electricity.

Yet despite these hardships, the people retain their warmth, faith and ability to laugh. One of the most rewarding and heartwarming aspects of my Hazard assignment was the easy humor of the lab staff. I don’t think that I have ever worked with people with whom I felt more comfortable, and we teased each other mercilessly as we worked.

I should also note that Hazard, Kentucky was the true birthplace of The Dukes of Hazzard. When the series was running, the Dukes visited every year to participate in the Fourth of July parade. The courageous teen who jumped into a swimming pool to rescue a drowning child was named an honorary Duchess of Hazard. Finally, Frank Gorman, who has been mayor of Hazard for more years than anyone can remember, drives a white Cadillac convertible identical to that driven by Boss Hogg in the series. His wife has one too. It is also worth noting that the entirety of the road winding up to his luxurious home on Gorman Ridge, high above the town, is kept mown by hand- at city expense.

With all its many facets of humor and tragedy, violence and spiritual richness, this year was a time of great personal growth, and I am grateful that being an itinerant pathologist allowed me to have these experiences. I look forward to more travels with Janie and my camera, and now cannot imagine working in an office in one place.

Note: All of the photographic images in this page are digital.

Reference:

Watman, Max. “Death of a Moonshiner.” http://www.gourmet.com/winespiritsbeer/2009/03/marvin-popcorn-sutton-death.

NOTE:

An abridged version of this article appeared in the December 2007 edition of LocumLife magezine; a full text version appeared in the 2009 edition of the King County Medical Journal.

Fo another author who beautifully conveys the “feel” of Applalachian life, try Kelli Haywood’s blog “A Mountain Mama.”